Confronting Behavior Bias

In Financial Projections (Part I of II)

This is a two-part article that considers the review and assessment of prospective financial information. Specifically, this discussion describes the behavioral bias that may influence financial projections. This discussion should inform any party involved in compiling or assessing financial projections. This discussion is particularly relevant for fiduciaries who may be involved in the transaction or other investment decision-making process.

Introduction

This discussion considers the review and assessment of financial projections that are prepared as part of a corporate transaction. This discussion may inform any party involved in compiling or assessing financial projections. This discussion may be particularly relevant to (1) fiduciaries who may be involved in the corporate transaction or other investment decision making process and (2) financial advisers to a fiduciary who assist in reviewing the financial aspects of the subject transaction.

For purposes of this discussion, the term “fiduciary” refers to parties that are not directly involved in the management and operations of the subject company that have duties of loyalty and care to subject company shareholders. This definition of fiduciary includes trustees of trusts and executors of estates that hold interests in private companies. Trustees may be appointed to oversee and administrate assets of retirement plans, charities, trust funds, and entities in bankruptcy. Independent board members are also included in our definition of fiduciary.

It is generally understood that corporate merger and acquisition transactions are risky. There are various biases that come into play with respect to merger and acquisition transactions. For better or worse, these biases generally tend to increase merger and acquisition activity. Bias does not discriminate—all parties to the transaction may be subject to the influence of bias.

When a fiduciary is involved in a corporate transaction, the fiduciary may be disadvantaged relative to other parties to the proposed transaction. This is because the fiduciary may have less information than other parties to a transaction. For example, shareholders that are also members of management will likely understand the company and the industry better than the fiduciary.

Often, the terms of the proposed transaction are brought to the fiduciary after the initial rounds of developing and structuring the proposed transaction (after feasibility, etc.). Other parties to the proposed transaction may be involved with the transaction from an early stage. Nevertheless, the fiduciary is expected to act in a prudent manner with respect to the proposed corporate transaction.

The fiduciary may retain a financial adviser to opine on the financial aspects of the proposed corporate transaction.

Financial projections are often prepared in corporate merger and acquisition transactions. The financial projections may be prepared by any party to the transaction. The financial projections are one of the primary inputs to the transactional valuation model, and they are generally used to support the proposed transaction price.

One of the roles of a fiduciary’s financial adviser (the financial adviser) is to review (and, in some cases, amend or even produce) financial projections. The financial projection review process is an element of the transactional valuation process.

This discussion draws from various aspects of behavioral finance that may improve the financial projections review process. This discussion provides a road map for the fiduciary and the financial adviser to discover potential forms of bias present in financial projections. This discussion also provides general guidance for assessing financial projections.

Forms of Behavioral Bias

This discussion on behavioral bias is based primarily on the work of Daniel Kahneman, PhD and Amos Tversky, PhD, which was published in Thinking, Fast and Slow (TFAS).1 Kahneman received the 2002 Nobel Prize in economic sciences for their pioneering work on decision making.

This discussion focuses on the biases in TFAS that could influence the assessment of financial projections and the decision of a fiduciary to accept a transaction, in general. Kahneman identifies common forms of bias, and he defines bias as systematic errors in judgment. In order to simplify two traits of thought, TFAS characterizes thought processes as either “fast” or “slow.”

The fast processes are the result of the automatic processes of so-called “System 1,” and the slow processes are the result of the controlled operations of so-called “System 2.” The two systems often work together to form a coherent interpretation of what is going on in the world at any instant.2

The unsolicited human “need” to form a coherent story often results in bias in decision making. Human minds are built to find links between events and reach conclusions even when there is no link. People are prone to apply causal thinking when statistical reasoning is more appropriate. These issues are especially present in the production and analysis of financial projections.

The following discussion explains some of the common forms of bias that may be considered when assessing financial projections. This list is not exhaustive.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias refers to the natural tendency to seek data that support current beliefs and opinions, as opposed to the general rule of science that a hypothesis is meant to be disproven. Confirmation bias results in (1) overweighting recent occurrences and (2) extreme and improbable events.

The Halo Effect

The halo effect is the tendency to like, or dislike, everything about a subject. The halo effect occurs because our mind has difficulty balancing the complexity of the world. For instance, it is difficult to comprehend that Hitler loved dogs and children. Humans tend to rely on our first impression and slant or omit future observations that do not comport with the initial impression.

One way that the halo effect can be overcome is by decorrelating error. In the context of a corporate transaction, this effect could be overcome by receiving independent judgments from parties involved (for instance, separately interviewing members of company management and soliciting individual input from all members prior to a meeting).

WYSIATI

What you see is all there is (WYSIATI) refers to the tendency to develop conclusions based only on the information that is at hand. It is often easier for human minds to construct a coherent story when there is less information. The quality and quantity of data is often irrelevant for constructing the story.

The example from TFAS asks, “Will Mindik be a good leader? She is intelligent and strong…” The automatic response to this question is “yes.” This would be a problem if the next two adjectives to describe Mindik were corrupt and cruel.3 One of the best ways to confront WYSIATI is to prepare a list of the characteristics needed to make the decision at hand.

In the corporate transaction context, the question could be, “What information do we need to indicate that this company is worthy of a long-term investment?”

The Law of Small Numbers

The law of small numbers refers to the failure to “think like a statistician.” Statisticians understand that small samples have greater risks of error. With smaller samples, there is greater difficulty to discern if there is a pattern in the data or whether the smaller sample is random. The illusion of patterns in small samples will often cause people to classify a random event as systematic.

As with the other biases, content of messages tends to be more important than reliability. It is often difficult to accept the randomness of events with respect to reviewing projected financial statements.

For instance, this bias is reflected in determining the growth trajectory of a company based on three years of historical financial statements, which have shown consistent revenue growth of approximately five percent, versus observing 10 years of historical financial statements with a greater standard deviation.

The Anchoring Effect

The anchoring effect describes the common human tendency to rely on the first piece of information offered (i.e., the anchor) when making decisions. Various studies have demonstrated that people rely on an anchor, even when the anchor has no bearing on the decision at hand.

In negotiations, the first price offered serves as an anchor price, which tends to affect the rest of the negotiations. A high anchor will result in a higher final transaction price, and a low anchor will result in a lower final transaction price. The primary advice offered to negate the anchoring effect is to reject the initial offering price if it is determined to be unreasonable.

In the context of financial projections, it is best practice to reject financial projections that are unreasonable and create a new set of financial projections rather than adjusting the original financial projections.

Representativeness

Representativeness refers to instances when we rely on intuitive impressions and neglect base-rate information. The example of representativeness in TFAS is: consider that a woman is reading the New York Times on a subway in New York City—is it more likely that she (1) has a PhD or (2) does not have a college degree.

Representativeness would say that she has a PhD; however, the base rate comparison of PhDs to nongraduates on New York subways is very unfavorable to this selection.

According to Kahneman, intuitive predictions should be adjusted by estimating the correlation between the intuitive prediction and the base rate. If the intuitive prediction is unsupported, the base rate should be relied on. “A characteristic of unbiased predictions is that they permit the prediction of rare or extreme events only when the information is very good.”4

To counter representativeness in financial projections, the expected growth rate in the projection should consider base rates that are observed in the industry and in the economy.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias refers to our tendency to produce simplified narratives of the past. Hindsight bias can simply be called the “I-knew-it-all-along” effect. It can lead an observer to assess the quality of a decision not by whether the process was sound, but by whether its outcome was good or bad.5

The hindsight bias often leads to overconfidence in forecasting. This is because “the idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained.”6

The Planning Fallacy

The planning fallacy occurs when forecasts (1) are unrealistically close to best-case scenarios and (2) neglect the base rate of similar cases.

The planning fallacy can be partially mitigated by (1) considering outside statistics and (2) including some estimate for “unknown unknowns” in the forecast.

Overconfidence

Overconfidence is often determined by the coherence of the story one has constructed, not by the quality and the amount of the information that supports the story.

Overconfidence and optimism can result in failure to consider outside forces such as competition and chance. Emotional, cognitive, and social factors can support exaggerated optimism, which may lead people to take high risks that they would avoid if they knew the probability of failure. High subjective confidence is not a trusted indicator of forecast accuracy (surprisingly, low confidence may be more informative).

One tool used to partially counter overconfidence is the premortem. A premortem asks the decision maker to develop a story based on the notion that the decision is a failure in one year. This practice gives voice to doubts. The alternate stories developed can be considered as part of the projected financial statement review process.

Understanding the Financial Projections

Financial projections are one of the primary inputs in many business valuation models. Financial projections directly influence the discounted cash flow (DCF) method of the Income Approach and often influence the Market Approach (due to using forward-looking pricing multiples or adjusting historical pricing multiples based on the subject company’s growth expectations).

Financial projections are one of two primary inputs for the Income Approach DCF method. Typically, the two primary Income Approach inputs are projected cash flow and the present value discount rate. In the DCF method, the financial adviser assesses the financial projections and selects a present value discount rate to apply to the projected cash flow.

Financial projections are a tool that is often used to assess business investments. The financial projections typically forecast the income statement, the balance sheet, and the cash flow statement for a set period.

Often, the financial projections reflect company management’s best thinking and do not incorporate alternative scenarios.

As discussed below, there are various ways to develop financial projections. Financial projections are developed using assumptions that reflect the developer’s expectations for the company’s performance. Regardless of how the financial projections are developed, every projection tells a story.

The Financial Projection Story

The statement, “every projection tells a story,” may appear obvious to some. The numbers in the financial projection are intended to demonstrate the initiatives undertaken by company management. The numbers do not inherently “tell a story,” but, if they are prepared correctly, they are based on a story that is being presented by the party that is proposing the transaction (i.e., not the fiduciary or the fiduciary’s financial adviser).

According to conventional wisdom, people tend to exercise right-brained or left-brained dominance in their personality, thinking style, and general approach to life. Analysts are subject to the same biases.

Right-brained analysts tend to favor anecdotes, experience, and behavioral evidence in assessing an investment, whereas left-brained analysts tend to favor spreadsheets, pricing data, and statistical measures in assessing an investment.

The right-brained analysts make decisions based on the story (loosely, the qualitative analysis), whereas left-brained analysts make investment decisions based on quantitative analysis.

A thorough review of financial projections involves understanding the story that the financial projections tell from qualitative and quantitative perspectives.

The first hurdle in reviewing financial projections is the understanding of how the projections were developed.

After understanding the development of the financial projections, the fiduciary and the financial adviser may ask the following questions:

- What is the story that the financial projections are telling?

- Is the financial story congruent with the vision of the company?

- Are there any alternative stories for the company that should be considered?

Development of the Financial Projections

An initial procedure that may be taken when assessing financial projections is understanding the projection development process. Interviewing the party who prepared financial projections can assist the fiduciary or the financial adviser in discovering projection bias.

The financial adviser may consider the following guideline questions when analyzing management-prepared financial projections.

- Who prepared the financial projections?

Understanding who prepared the financial projections can assist in determining the reliability of the projections. The financial adviser may want to consider any potential biases or conflicts of interest associated with the party that developed the financial projections. Financial projections prepared by a party with financial ties to the transaction may be subject to various forms of bias.

It may be important to consider who had input on the financial projections, and how they may have influenced the projections. For example, a salesperson’s input for projected revenue figures may differ from an accountant’s input.

- For what reason were the financial projections produced?

A financial adviser may consider the purpose of the projections. Financial projections may be prepared for transaction purposes, budgeting, sales goals, obtaining credit, and so on. The purpose of the financial projections may affect the detail and the characteristics of the projections.

For example, financial projections developed for the purpose of marketing a company for an acquisition may be more detailed and aggressive than projections provided to a bank for obtaining a credit facility.

- How often are financial projections prepared?

If company financial projections are prepared regularly, then the company has the benefit of experience in producing financial projections and, therefore, they may be more reliable than financial projections prepared by a company for the first time.

In addition, historically prepared financial projections may be compared to actual results in order to indicate how a company’s expectations typically compare to actual outcomes. However, if there are material changes in projections prepared for a deal compared to historically prepared projections, then the benefit of frequency is lost.

- How were the financial projections prepared?

There are various methods for preparing projections, each with the potential of incorporating different bias or levels of conservatism.

One example is the top-down versus bottom-up approach. A top-down approach evaluates the market as a whole and identifies a company’s target market, including the potential market share and growth. A bottom-up approach is typically more detailed and starts by determining spending levels and sales forecasts of each department.

Compared to looking at the overall market, a bottom-up approach may be more reliant on existing customers and leads. Since a bottom-up approach is more reliant on existing customers, it may not consider the potential market opportunities that would produce a more aggressive forecast.

What were the considerations for the economic, industry, and other value drivers? How do value drivers connect to the story of the projections?

- How does management characterize the financial projections?

It is often helpful to understand the company management’s characterization of the financial projections.

Variables in the Story

The financial projection story should be consistent for economic, industry, and company-specific factors. This discussion provides examples of these factors that may be considered in assessing the projections.

Economic Considerations

A financial adviser may want to research historical, current, and forecasted economic conditions and indicators, depending on how significantly the economy may influence the earning ability of a firm.

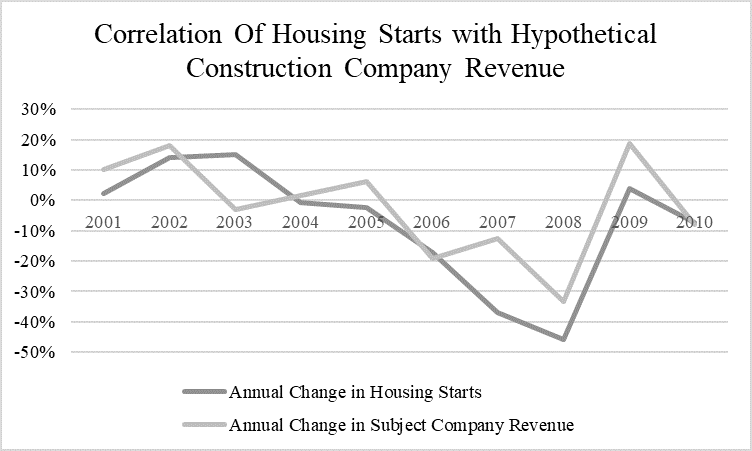

Through research, a financial adviser may identify specific economic trends that are indicative of the demand for products or services offered by a subject company. For example, an increase in housing starts may indicate an increase in demand for a residential construction company.

After determining which economic indicators may influence the earning ability of the company, the financial adviser may compare historical company data with historical economic performance.

Figure 1 is an illustrative example of a correlation analysis that compares the annual change in U.S. housing starts with the annual change of historical revenue of a hypothetical residential construction company.7

As can be seen in Figure 1, there appears to be a correlation between the annual change in housing starts and the annual change in revenue of the hypothetical construction company.

Figure 1: Correlation of Housing Starts with Hypothetical Construction Company Revenue

After determining there is a correlation between an economic indicator and historical company performance, the financial adviser can research the outlook of that economic indicator. A comparison of the outlook of an economic indicator and projected financial statements could assist the financial adviser in determining the reasonableness of the financial projections.

It may also be helpful to ask the party that prepared the projections if the outlook of any specific economic indicators was considered during the projection development process.

It may also be useful to perform additional research on a local economy. If a company’s clients are predominately located in the southern U.S., then it may be helpful to research the outlook of the southern U.S. economy.

The growth rate of the economy may serve as a base rate for the subject company.

Industry Considerations

The industry in which a company operates may significantly influence future cash flow and growth potential. A general knowledge of the industry in which the subject interest operates can be helpful when assessing financial projections. It may even be necessary to consider researching industries in which major customers or suppliers of the subject company operate, as they may also influence the earning potential of the company.

The degree of detail and analysis concerning the company’s industry may vary depending on the following factors:

- The industry’s level of influence on the subject company

- The amount of available industry data.

A few questions that the financial adviser may consider8 include the following:

- Who makes up the industry? Are there a few companies that influence the industry?

An industry that is fragmented is unlikely to be as competitive as a highly concentrated industry. In a concentrated industry, financial results and analyst estimates may be strong indicators to consider when assessing financial projections.

- Is the industry cyclical?

A cyclical industry is more dependent on the general economy than a less cyclical industry. If an industry is determined to be cyclical, then additional attention to economic indicators and forecasts may need to be considered when assessing financial projections.

- Is it a new industry with several new entrants, or is it a mature industry that has reached its saturation point?

A company operating in a mature industry will typically anticipate lower levels of growth than a company in an emerging industry. If a company in a highly saturated industry anticipates growth that is inconsistent with the industry, then additional questions may need to be asked.

- What are the barriers to entry, if any, into the industry?

Existing firms benefit from barriers of entry into an industry, limiting competitive risks, while a newer company may be disadvantaged in an industry with high barriers of entry.

- Is the industry self-contained or is it dependent on another industry?

The amount of dependence an industry has on another industry can be a signal that the outlook of more than one industry may be considered when assessing projections.

- What is a normal level of capital expenditures in the industry?

Different industries require various levels of capital expenditures in order to operate effectively. Determining what is an appropriate level of capital expending in order to operate efficiently and obtain projected cash flow may be considered in a projection analysis.

- Is the industry dependent on new technology?

Companies that operate within an industry that is highly dependent on new technology are likely to require more research and development related expenditures.

- Is the industry anticipated to change?

If a company is not aligned for anticipated change, then it may not be able to meet its forecast goals. The ability of a company to adapt and anticipate change may significantly impact its ability to produce future cash flow.

- What is the forecast of growth for the industry?

The growth of a company can often be tied to the growth of the industry in which it operates. Therefore, considering the growth of an industry is often a component of assessing financial projections.

It is noteworthy that these questions are not all inclusive and may be considered as basic guidelines or ideas.

A simple way in which the financial adviser can compare the performance of the company with the performance of the industry is by observing changes in stock price of comparable public companies (or an industry exchange traded fund) with the historical performance of the subject company. This comparison may assist the financial adviser in determining if there is a strong correlation between:

- Industry performance and

- The performance of the subject company.

Depending on how strong of a correlation there is between the industry and the subject company, the financial adviser may want to compare the industry outlook with the projections of the subject company. If a financial adviser observes that an industry is anticipated to experience an annual revenue decline of five percent, then it may raise questions when the company within that industry projects revenue growth of 10 percent.

However, there may be company-specific factors that justify why a company may perform better than the industry in which it operates.

In Part II, the authors discuss company-specific considerations and quantitative factors to check on bias.

Notes:

- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013).

- Ibid., 13.

- Ibid., 85.

- Ibid., 192.

- Ibid., 203.

- Ibid., 218.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Housing Starts: Total: New Privately-Owned Housing Units Started, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/HOUST, January 22, 2019.

- Some of these questions are taken from Gary R. Trugman, Understanding Business Valuation: A Practical Guide to Valuing Small to Medium Sized Businesses, 5th ed.(New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 2017), 162.

Kyle Wishing is a manager in the Atlanta office of Willamette Management Associates.

Mr. Wishing can be contacted at (404) 475-2309 or by e-mail to kjwishing@willamette.com.

Ben Duffy is a manager in the Atlanta office of Willamette Management Associates.

Mr. Duffy can be contacted at (404) 475-2326 or by e-mail to brduffy@willamette.com.