Best Practices for Estimating the Company-Specific Risk Premium

(Part II of IV)

This is the second of a four-part article that sets forth best practices for estimating the company-specific risk premium. The first part of this series summarized where and how the CSRP applies in the various generally accepted cost of capital measurement models. This second part summarizes (1) the concepts of systematic risk and unsystematic risk and (2) the considerations of unsystematic risk in the analyst’s CSRP estimate.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Best Practices for Estimating the Company-Specific Risk Premium (Part I of IV)

[/su_pullquote]

Introduction

This discussion is the second of a four-part series that summarizes best practices in the analyst’s estimate of the company-specific risk premium (CSRP). Regarding private company business valuations, the CSRP is a consideration in every generally accepted cost of capital measurement model. Such cost of capital measurement models are applied to inform the analyst’s selection of the present value discount rate or direct capitalization rate. Such discount rates and capitalization rates are applied in the various income approach business valuation methods.

The first part of this series summarized where and how the CSRP applies in the various generally accepted cost of capital measurement models. This second part summarizes (1) the concepts of systematic risk and unsystematic risk and (2) the considerations of unsystematic risk in the analyst’s CSRP estimate.

Systematic Risk and Unsystematic Risk

To understand the importance of both the Sp and the CSRP in measuring the Ke for the analysis of a private company, it may be helpful to identify the differences between systematic risk and unsystematic risk. According to the textbook Valuing a Business:[1]

… systematic risk is the uncertainty of future returns resulting from the sensitivity of the return on the subject investment to movements in the return on the investment market as a whole. Unsystematic risk is a function of characteristics of the industry, the individual company, and the type of investment interest.

The basic CAPM assumes that the Ke risk premium component is a function of the investment’s systematic risk only. One fundamental principle of the basic CAPM is that the investor expects a return on investment assuming that the investment is both (1) perfectly liquid and (2) part of a perfectly diversified portfolio of liquid investments. In addition, another fundamental principle of the basic CAPM is that beta encompasses all the risk inherent in the subject investment. Because unsystematic risk is associated with the characteristics of the individual investment, the CAPM does not incorporate an adjustment for CSRP.

However, MCAPM was developed as a method for measuring Ke for an investment that is either—or both (1) not perfectly liquid and/or (2) not part of a perfectly diversified portfolio of liquid investments. In other words, MCAPM is applicable to the Ke measurement for a private company investment.

Unsystematic risk is incorporated in the MCAPM measurement of Ke by including the consideration of both Sp and CSRP (or, collectively, alpha).

Size-Related Risk Premium

In addition to the ERP, the MCAPM also incorporates consideration of an Sp (this Sp is sometimes also referred to as a small company risk premium). For a particular size of subject investment, the Sp represents the difference between the actual historical excess return and the excess return predicted by beta.

This “size effect” is based on the empirical observation that companies of smaller size are generally associated with greater investment risk and, therefore, have to provide a greater rate of return on investment in order to attract equity investors.

Company-Specific Risk Premium

The CSRP is the risk premium associated with the level of unsystematic risk inherent in a particular private company. The CSRP can be positive or negative depending on the facts and circumstances of the private company. The CSRP represents the additional risk premium required to compensate an equity investor for the uncertainty of investing in a particular private company.

The following discussion considers (1) the conceptual principles for the CSRP component of the Ke and (2) the practical procedures for estimating the CSRP component of the Ke.

Selection of a Company-Specific Risk Premium

In the professional literature related to investment analysis and portfolio management, “company-specific risk” is interchangeably referred to as “investment-specific risk,” “property-specific risk,” “nonsystematic risk,” “unsystematic risk,” “nondiversifiable risk,” and “idiosyncratic risk.”

This discussion sometimes uses the term “investment-specific risk.” However, the term “company-specific risk” is more frequently used in the valuation professional literature. Therefore, this discussion generally uses the term “company-specific risk.”

Consideration of a Company-Specific Risk Premium

When estimating the discount rate or capitalization rate related to an investment, the CSRP is generally the last component the analyst applies when measuring the Ke. The CSRP is the component of risk that makes an investment (1) unique and (2) different from other benchmark investments that may be used to measure private company capitalization rates, valuation pricing multiples, and/or other pricing metrics.

The inclusion of a CSRP in the Ke measurement is a generally accepted valuation procedure. However, a few issues complicate the development of the CSRP estimate. The issues that can complicate the CSRP estimate include risk (1) identification, (2) measurement, and (3) correlation with the appropriate incremental rate of return.

Because the CSRP is based on company-specific risk, there is no database, empirical study, measurement model, formula, or the like that analysts apply to calculate a CSRP for an individual investment. Therefore, while both qualitative analysis and quantitative empirical data proxies may be useful in developing the CSRP estimate, the estimate is ultimately a matter of the analyst’s professional judgment.

In many (but not all) transactions involving business interests, investors (or potential willing buyers) expect to be compensated for the assumption of company-specific risk. However, investors (or potential willing buyers) do not expect to be compensated for a CSRP in transactions where company-specific risk can be easily diversified away.

The CAPM was originally developed to estimate the Ke of a well-diversified portfolio of perfectly liquid investments. Accordingly, the CAPM is less applicable for estimating the Ke of a nondiversified portfolio of illiquid investments. With the development of the MCAPM, a CAPM-based model can be applied to estimate a discount rate or capitalization rate for purposes of a private company valuation. This is because the MCAPM incorporates a component for the increased risk associated with private company investment factors—factors that are not mitigated by perfect diversification and perfect liquidity.

For private company ownership interests that lack the risk-mitigating influences of liquidity, diversification, and/or limited liability, company-specific risk cannot be diversified away. In contrast, the expected Ke of an investment that does possess the risk and expected return attributes of diversification and liquidity is likely not influenced by a CSRP.

The CSRP is considered directly in the application of the income approach when analysts select a discount rate or capitalization rate for the valuation of a private company ownership interest.[2] Further, the CSRP is considered indirectly in the application of the market approach and the asset-based approach in the valuation of a private company ownership interest.

The CSRP is considered directly in the business valuation income approach when analysts estimate the Ke for purposes of calculating (1) a cash-flow-based (enterprise) discount rate or capitalization rate or (2) a net-income-based (equity) discount rate or capitalization rate.

The CSRP is considered indirectly in the business valuation market approach when:

- Selecting guideline publicly traded companies and guideline merger and acquisition transactions and

- Extracting subject-interest-specific pricing multiples from the selected guideline publicly traded companies or the guideline merger and acquisition transactions.

The CSRP is considered indirectly in the business valuation asset-based approach when:

- Measuring any intangible value in the nature of goodwill, particularly through the application of the capitalized excess earnings method (CEEM) of intangible property valuation or

- Measuring any economic obsolescence in the cost approach valuation of the private company real estate and personal property, particularly through the application of the capitalization of income loss method (CILM) of economic obsolescence measurement.

To a certain extent, the magnitude of the selected CSRP may be influenced by the purpose of the valuation.[3] For example, the selection of the CSRP to be considered in the valuation may be influenced by the following considerations:

- The statutory, regulatory, judicial, or other standard of value selected—or required—for the valuation assignment (e.g., fair market value, fair value, investment value).

- The statutory, regulatory, judicial, or other level of value selected—or required—for the valuation assignment (e.g., controlling marketable, noncontrolling marketable, controlling nonmarketable, noncontrolling nonmarketable).

- The statutory, regulatory, judicial, or other premise of value selected—or required for—the valuation assignment (e.g., value in continued use as a going concern, value in exchange as part of a disposition of assets).

Furthermore, the consideration of CSRP with regard to a private company valuation may be informed by legal instructions from legal counsel. That is, legal counsel may instruct the analyst as to the relevant statutory authority, judicial precedent, or administrative rulings. For example, the Delaware Court of Chancery (the “Chancery Court”) has opined on the inclusion of a CSRP in numerous fair-value-related shareholder appraisal rights and shareholder oppression matters. In these judicial decisions, the Chancery Court has generally disallowed the inclusion of a CSRP in the Ke measurement regarding fair value valuations.

As a result, in such a fair value valuation shareholder dispute pending before the Chancery Court, legal counsel may instruct the analyst not to include the CSRP in the discount rate or capitalization rate analysis.

The following discussion summarizes (1) the analyst’s qualitative considerations related to the CSRP and (2) the analyst’s quantitative considerations related to the CSRP.

Quantification of a Company-Specific Risk Premium

Analysts may rely on a qualitative analysis to develop the CSRP estimate. The following sections present (1) the qualitative factors that analysts may consider and (2) the qualitative procedures that analysts may apply to those factors in order to develop the CSRP estimate.

Qualitative Factors

Three sets of qualitative factors that analysts consider are presented below. For purposes of this discussion, these factors are categorized as follows:

- National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA) factors

- Subject company competitive analysis factors

- Subject company functional analysis factors

NACVA Factors

In its various publications, NACVA has recommended various factors that analysts may consider developing the CSRP estimate. The factors may be grouped in the following six categories:

- Competition

- Financial strength

- Management ability and depth

- Profitability and stability of earnings

- National economic effects

- Local economic effects

NACVA indicates that analysts make individual quantitative and qualitative assessments within each of the first four categories of CSRP factors. In order to estimate the CSRP, analysts assign a specific point value (ranging from 1 point for low risk to 10 points for high risk) to each factor. This point assignment is based on the analyst’s professional judgment with regard to the private company operations.

The final two categories are economic factors that analysts assign points of minus one, plus one, or zero—based on a strong economy, weak economy, or neutral economy, respectively. These categories and factors are also scored based on the analyst’s professional judgment.

Finally, analysts calculate the sum of (1) all of the point values in the first four categories (weighted by the number of individual factors in each category) and (2) all of the point values in the last two categories. This summation provides an indication for analysts to consider in developing the judgment-based CSRP estimate.

The NACVA analysis is considered a “numerical procedure.” An example of a numerical procedure is presented later in this discussion.

Private Company Competitive Analysis Factors

The analyst’s strategic assessment of the private company’s competitive position provides an analysis structure—based on a competitive advantage and strategy analysis—for estimating the CSRP. This competitive analysis aggregates the CSRP factors into three categories that consider the company’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT). These categories of factors are presented as follows:

- Macroenvironmental factors

- Industry factors

- Company factors

The competitive analysis includes a subgroup of factors for analysts to consider within each of the three categories. This competitive analysis is based on an application of Michael Porter’s “Five Forces” strategic planning and analysis model. In this procedure for analyzing the CSRP, a competitive analysis should be part of the analyst’s judgment in developing the CSRP estimate.

The competitive analysis may be applied by considering any of the qualitative factor analysis procedures presented later in this discussion.

Private Company Functional Analysis Factors

A functional analysis considers the assets employed, the functions performed, and the risks assumed by the private company. Such a functional analysis includes the analyst’s consideration of various categories of individual quantitative and qualitative CSRP factors.

One of the functional analysis categories of CSRP considerations relates to the following private company risk factors:

- Economy risk

- Operating risk

- Asset risk

- Market risk

- Regulatory risk

- Business risk

- Financial risk

- Product risk

- Technological risk

- Legal risk

Such a functional analysis further presents a category of CSRP considerations relating to the following private company nonfinancial factors:

- Economic conditions

- Location of business

- Depth of management

- Barriers to entry into market

- Industry conditions

- Competition

- Quality of management

- The bottom line

The analyst’s company-specific assessment of all these factors is relevant to developing the CSRP estimate. Moreover, like all of the CSRP factors considered, analysts rely on informed professional judgment when developing the CSRP estimate.

The following section presents three practical procedures that analysts may consider to analyze and document the qualitative factors presented above.

Documentation Procedures of a Qualitative Factor Analysis

Some analysts apply three procedures for (1) estimating a CSRP based on the qualitative analysis of the company-specific risk factors and (2) documenting the analyst’s due diligence and final CSRP estimate.

These three documentation procedures are sometimes called (1) the plus/minus procedure, (2) the numerical procedure, and (3) the listing procedure.

All three of these procedures start with a listing of the relevant CSRP factors selected by the analyst. These due diligence and analysis documentation procedures are discussed below.

The Plus/Minus Procedure

In the plus/minus (or +/-) documentation procedure, analysts indicate either a “+” notation or a “-” notation next to the test of each factor considered. The plus notation indicates that the factor increases the amount of the CSRP; the minus notation indicates that the factor decreases the amount of the CSRP. A blank notation indicates that the factor has a neutral impact on the amount of the CSRP.

Double or triple notations (e.g., ++ or —) indicate that the individual factor has a particularly positive or a particularly negative impact on the quantum of the CSRP. Each plus/minus notation, however, does not necessarily represent one percentage point.

Ultimately, the quantum of the CSRP is based on the analyst’s professional judgment. The CSRP estimate should not be considered as the mathematical summation of “plus” and “minus” indications.

The Numerical Procedure

Using the numerical documentation procedure, analysts assign a specific percentage number to each CSRP factor considered.

If the analyst assigns “2.0” to a particular factor, that indicates that the analyst adds two percentage points to the quantum of the CSRP factor. If the analyst assigns “(1.0)” to a particular factor, that means that the analyst subtracts one percentage point from the quantum of the CSRP. And, if the analyst assigns “0” to a particular factor, that factor has no impact on the quantum of the CSRP.

In contrast to the previously described “plus/minus” procedure, in the numerical procedure, the analyst’s CSRP estimate is informed by the numerical summation of all of the individual values for each CSRP factor.

The Listing Procedure

Applying the listing documentation procedure, analysts list all of the negative—and all of the positive—company-specific risk factors. Analysts do not assign a numerical quantum to either the negative factors or the positive factors. And analysts do not indicate the relative importance of any individual CSRP factor.

Applying the listing procedure, the analyst estimates the CSRP based on professional judgment.

Example of Qualitative Factor Analysis

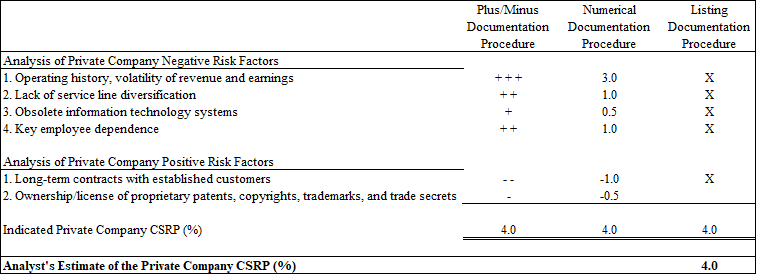

Table 1 depicts the three above-mentioned CSRP documentation procedures as applied to a simplified illustrative private company valuation. In this illustrative example, the analyst identified the strategic, financial, and operational risk factors that most affect the company.

Table 1: Illustrative Private Company Valuation Analysis Documentation of the Analyst’s CSRP Assessment Example of Qualitative Factor Analysis

Based on a functional analysis, the analyst assessed each positive and each negative company-specific risk factor affecting the illustrative company. In Table 1, the analyst prepared three alternative documentation procedures related to the subject-company-specific risk due diligence and analysis.

Table 1 illustrates the three alternative documentation formats or procedures (i.e., plus/minus, numerical, and listing) of the analyst-selected CSRP factors in this illustrative company valuation. In this example, regardless of the due diligence documentation procedure selected, the analyst consistently estimated 4 percent as the CSRP.

In this illustrative example, the analyst concludes 4 percent the CSRP estimate.

Summary

The CSRP estimate is an important component in the cost of capital measurement for any private company valuation. The CSRP is often a source of disagreement between analysts preparing valuations of private company business interests. This second of a four-part discussion summarized (1) the generally accepted cost of capital measurement models, (2) the impact of the CSRP on the cost of capital measurement, and (3) the qualitative factors that analysts may consider in developing the CSRP estimate.

The next part of this discussion will present various quantitative analyses that analysts may consider as a proxy, benchmark, or approximation in the private company CSRP estimate. These quantitative analyses are intended to be considered by analysts as a proxy, benchmark, or approximation to provide general guidance in developing the CSRP estimate.

[1] Shannon P. Pratt and Alina V. Niculita, Valuing a Business: The Analysis and Appraisal of Closely Held Companies, 5th ed. (NY: McGraw Hill Companies, 2008), 185.

[2] CSRP may also be relevant when valuing real property, personal property, and other types of illiquid investments. When applying an investment-specific risk premium in analyses where the subject to valuation is not a business interest, similar considerations should be made with regard to the (1) validity of the investment-specific risk premium, (2) the legal/statutory limitations on the use of an investment-specific risk premium, and (3) appropriate level of the subject- investment-specific risk premium.

[3] The inclusion of a CSRP in an analyst’s assignment is not necessarily limited to valuations. The CSRP may also be applied in damages engagements, transfer price engagements, and numerous other analyst engagements.

Robert Reilly, CPA, ASA, ABV, CVA, CFF, CMA, is Managing Director of Willamette Management Associate’ Chicago offices. His practice includes business valuation, forensic analysis, and financial opinion services.

Mr. Reilly has performed the following types of valuation and economic analyses: economic event analyses, merger and acquisition valuations, divestiture and spin-off valuations, solvency and insolvency analyses, fairness and adequacy opinions, reasonably equivalent value analyses, ESOP formation and adequate consideration analyses, private inurement/excess benefit/intermediate sanctions opinions, acquisition purchase accounting allocations, reasonableness of compensation analyses, restructuring and reorganization analyses, tangible property/intangible property intercompany transfer price analyses, and lost profits/reasonable royalty/cost to cure economic damages analyses.

He has prepared these valuation and economic analyses for the following purposes: transaction pricing and structuring (merger, acquisition, liquidation, and divestiture); taxation planning and compliance (federal income, gift, estate, and generation-skipping tax; state and local property tax; transfer tax); financing securitization and collateralization; employee corporate ownership (ESOP employer stock transaction and compliance valuations); forensic analysis and dispute resolution; strategic planning and management information; bankruptcy and reorganization (recapitalization, reorganization, restructuring); financial accounting and public reporting; and regulatory compliance and corporate governance.

Mr. Reilly can be contacted at (773) 399-4318 or by e-mail to rfreilly@willamette.com.

Connor Thurman is a senior associate with Willamette Management Associates. He performs the following types of valuation and economic analysis assignments: valuation of fractional ownership interests in businesses, forensic analysis, valuation of intangible assets and intellectual property, lost profits/economic damages analysis, and appraisal reviews.

Mr. Thurman prepares these valuation and forensic analyses for the following purposes: taxation planning and compliance (federal income, state and local property tax, transfer tax), forensic analysis and dispute resolution, marital dissolution, strategic information and corporate planning, ESOP transactions and financing, and ESOP-related litigation.

He performs these valuations for the following types of business entities and securities: closely held corporation business enterprises, closely held corporation noncontrolling ownership interests, various classes of common/preferred stock, general and limited partnership interests, professional service corporations, professional practices, and limited liability companies.

Mr. Thurman has performed these valuations for clients in the following industries: assisted living facilities, banking, coal power, electrical equipment manufacturers, electric utilities, food distribution, forestry products, grocery stores, logging, marijuana dispensaries, medical practices, natural gas distribution, natural gas power, natural gas transmission, oncology centers, railroads, real estate development, real estate holding, sawmills, telecommunications, transportation, travel agencies, and wineries.

Mr. Thurman can be contacted at (503) 243-7514 or by e-mail to cjthurman@willamette.com.