Cost Approach to Intellectual Property Valuation

Part III: Practical Procedures

Valuation analysts are often called on to value intellectual property for various transaction, taxation, financial accounting, corporate planning, litigation, and other reasons. In this Part III of this series, the discussion focuses on the practical measurement procedures related to the application of the cost approach in the intellectual property valuation.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]

Cost Approach to Intellectual Property Valuation Part I: Conceptual Principles

Cost Approach to Intellectual Property Valuation Part II: Valuation Methods[/su_pullquote]

Introduction

Valuation analysts (analysts) are often called on to value intellectual property for various transaction, taxation, financial accounting, corporate planning, litigation, and other reasons. For purposes of this four-part discussion, the term intellectual property includes the following four categories of intangible property: trademarks, patents, copyrights, and trade secrets. Analysts are also often called on to conclude an arm’s-length price for intellectual property for transfer pricing purposes. Additionally, analysts are often called on to measure damages related to intellectual property (including the cost to cure damages) for breach of contract claims and infringement (and other tort) claims.

This Part III of this four-part discussion focuses on the practical measurement procedures related to the application of the cost approach in the intellectual property valuation.

Comparisons of Historical Cost, Replacement Cost New, and Value

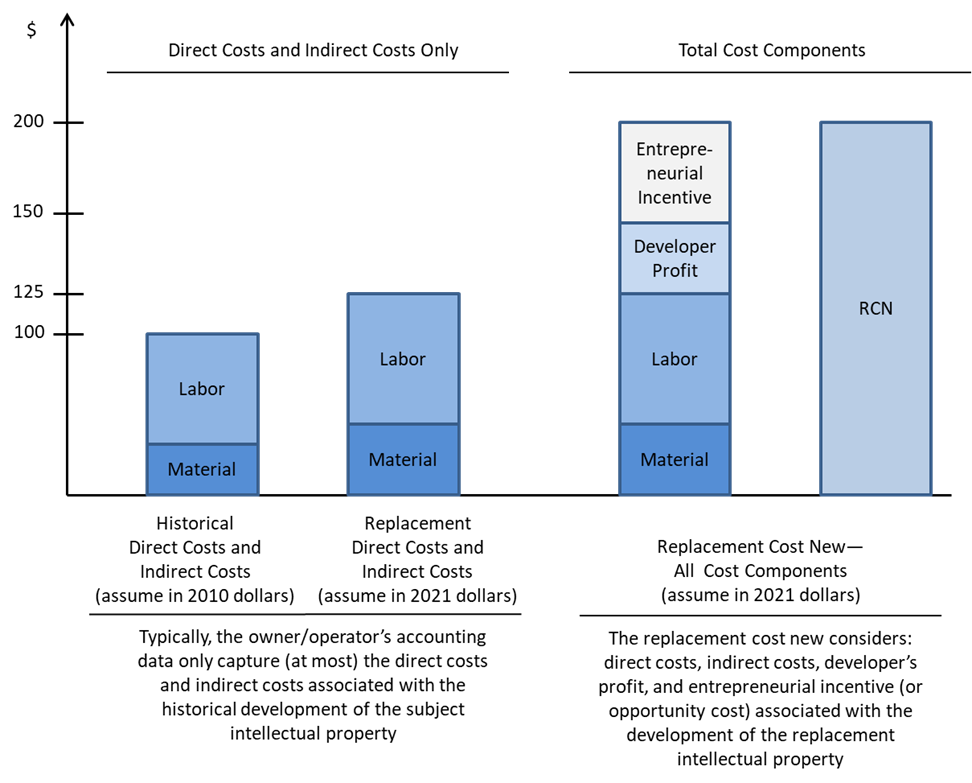

As described in part two of this discussion, all cost approach cost metrics typically consider four cost components: direct costs, indirect costs, developer’s profit, and entrepreneurial incentive. Each of these cost categories is typically incurred by the owner/operator in the intellectual property development process. Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of these four cost categories on a historical cost (or financial accounting) basis compared to on a replacement cost new (RCN) basis. This figure helps to illustrate the relationship between (1) the intellectual property historical cost and (2) the intellectual property RCN. Figure 2 also helps to illustrate the relationship between (1) the intellectual property RCN and (2) the intellectual property value.

Figure 1 illustrates the consideration of direct costs (such as direct material and direct labor) and indirect costs (such as consulting fees and legal fees) and of developer’s profit and entrepreneurial incentive in the cost approach valuation of an illustrative intellectual property. Figure 1 also considers the comparison of historical costs to the current (as in, valuation date) RCN.

Figure 1: Comparison of Historical Cost to RCN in the Intellectual Property Development Process

As presented in Figure 1, the total of the historical direct costs and indirect costs were $100 when the illustrative intellectual property was originally developed in, say, 2010. In Figure 1, the total of the current—or replacement—direct cost and indirect cost components is $125, as of a 2021 valuation date.

Figure 1 illustrates how the owner/operator’s historical accounting data typically do not consider developer’s profit or entrepreneurial incentive cost components. Typically, this statement is true even though the owner/operator did keep accurate track of the historical (i.e., in 2010) direct (including direct material and direct labor) and indirect (including consulting fees and legal fees) development costs.

The 2021 developer’s profit and entrepreneurial incentive cost components (estimated here at $75) are then added to the 2021 direct and indirect cost components (estimated here at $125). The sum of all of these four cost components (estimated here at $200) is the 2021 RCN for the intellectual property.

The cost components represented in Figure 1 are typically considered as capitalizable costs (i.e., capital expenditures), and not as period costs (i.e., expenses). The costs considered in the application of the cost approach to property valuation should not be considered either pre- or post-tax expenses. Rather, the costs considered in the application of the cost approach to property valuation should be considered as capitalizable expenditures. There is no “tax-affecting” that should be applied to the development of the cost metrics that are considered in the intellectual property cost approach valuation analysis.

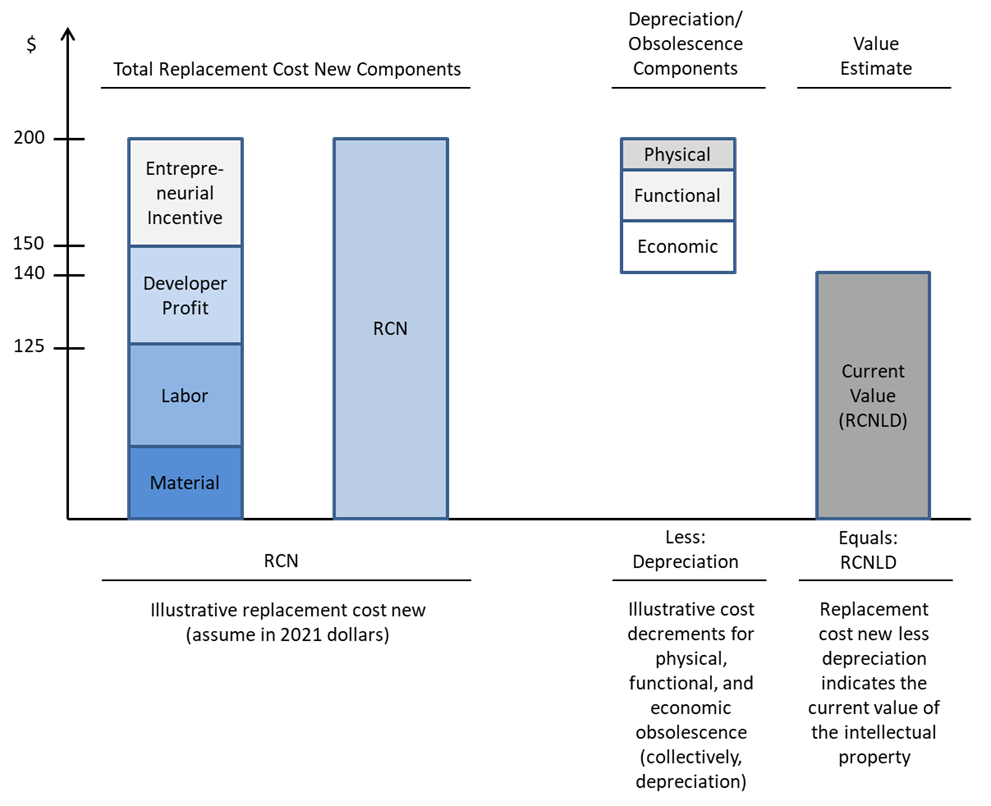

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between (1) RCN and (2) replacement cost new less depreciation (RCNLD). Figure 2 presents the intellectual property RCN as $200. This $200 RCN amount is the same RCN estimate as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 2: Comparison of the RCN to Current Value in the Intellectual Property Development Process

To estimate the intellectual property current value (or its RCNLD), the total amount of depreciation (including all obsolescence components) is subtracted from the RCN estimate. The three depreciation components include physical deterioration (typically a de minimis consideration for an intellectual property), functional obsolescence, and economic obsolescence. In Figure 2, the sum of these three depreciation components is $60. The intellectual property RCNLD is calculated as follows:

Cost Approach—RCNLD Method Analysis

$200 Intellectual property RCN

– 60 Less total depreciation

$140 Intellectual property RCNLD

Figure 2 presents the current value (or the RCNLD) of this hypothetical intellectual property to be $140. The RCNLD (and not the RCN) of the hypothetical intellectual property provides the cost approach value indication.

Functional Obsolescence Illustrative Example

Part II of this four-part discussion described the identification and measurement of the functional obsolescence component of depreciation in the application of the RCNLD valuation method. The following simplified example of the Alpha Manufacturing Company (Alpha) presents an illustration of the measurement of functional obsolescence in the RCNLD method valuation of internally generated computer software intellectual property. This illustrative intellectual property includes the software copyrights and trade secrets content.

To illustrate the process of functional obsolescence measurement, let’s assume that Alpha operates internally developed software related to its billing and receivables accounting function. Let’s assume this internally developed software was written in COBOL, a third-generation programming language. Alpha’s other customer records software and all of its administrative software are all written in Java or in C++ (or in some other fourth- and fifth-generation programming language).

Alpha management plans to replace the actual billing and receivables software with new state-of-the-art customized software. However, for the next five years, the Alpha IT department simply will not have the resources available to complete the new software development project.

In the meantime, Alpha has to employ a COBOL programmer in order to maintain the current billing and receivables software system. When a new software system is developed, this COBOL programmer position will be eliminated. The full absorption cost of the current COBOL programmer is $100,000 per year.

Let’s assume that an analyst is retained by Alpha management to estimate the fair market value of the copyrights and trade secrets intellectual property related to the billing and receivables software as of December 31, 2020. Alpha management wants to know the current value of that software-related intellectual property for corporate planning purposes. The analyst decides to apply the cost approach and the RCNLD method to value this software-related intellectual property.

Let’s assume that the analyst concluded that the RCN for the current billing and receivables software system is $1.2 million. The RCN for the new customized software system will be much greater than $1.2 million. To simplify this illustrative example, let’s assume that there is no physical depreciation or economic obsolescence related to the current computer software.

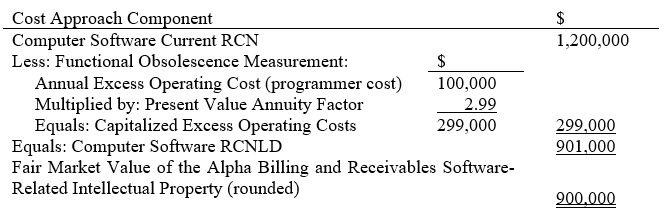

The capitalized excess operating cost method to measure functional obsolescence was described in Part II of this four-part discussion. Based on the application of that functional obsolescence measurement method, the analyst developed an RCNLD analysis and estimated the value of the current COBOL software intellectual property as summarized in Exhibit 1. In the Exhibit 1 capitalized excess operating cost method analysis, the 2.99 present value annuity factor is based on (1) an assumed five-year UEL for the actual software and (2) an assumed 20 percent (pretax) present value discount rate.

Theoretically, the analyst—if applying consistent valuation variables—would conclude the same value indication for the same intellectual property no matter which functional obsolescence measurement method he or she applies. The intellectual property RCNLD should be the same whether the analyst applies the excess capital cost method or the capitalized excess operating cost method to measure the Alpha intellectual property functional obsolescence.

Exhibit 1: Alpha Manufacturing Company Billing and Receivables Computer Software Copyrights and Trade Secrets Intellectual Property

Cost Approach—RCNLD Method

As of December 31, 2020

Based on the application of the cost approach and the RCNLD method, the analyst concluded that the fair market value of the Alpha software-related intellectual property, as of December 31, 2020, was $900,000.

Summary

This Part III of our four-part discussion summarized many of the practical measure procedures related to the application of the cost approach to intellectual property valuation. Part IV will present several illustrative examples of intellectual property cost approach valuation analyses.

Robert Reilly, CPA, ASA, ABV, CVA, CFF, CMA, is a Managing Director in the Chicago office of Willamette Management Associates, a Citizens company. His practice includes valuation analysis, damages analysis, and transfer price analysis.

Mr. Reilly has performed the following types of valuation and economic analyses: economic event analyses, merger and acquisition valuations, divestiture and spin-off valuations, solvency and insolvency analyses, fairness and adequacy opinions, reasonably equivalent value analyses, ESOP formation and adequate consideration analyses, private inurement/excess benefit/intermediate sanctions opinions, acquisition purchase accounting allocations, reasonableness of compensation analyses, restructuring and reorganization analyses, tangible property/intangible property intercompany transfer price analyses, and lost profits/reasonable royalty/cost to cure economic damages analyses.

Mr. Reilly has prepared these valuation and economic analyses for the following purposes: transaction pricing and structuring (merger, acquisition, liquidation, and divestiture); taxation planning and compliance (federal income, gift, estate, and generation-skipping tax; state and local property tax; transfer tax); financing securitization and collateralization; employee corporate ownership (ESOP employer stock transaction and compliance valuations); forensic analysis and dispute resolution; strategic planning and management information; bankruptcy and reorganization (recapitalization, reorganization, restructuring); financial accounting and public reporting; and regulatory compliance and corporate governance.

Mr. Reilly can be contacted at (773) 399-4318 or by e-mail to RFReilly@Willamette.com.