Economic Obsolescence Measurement Best Practices

(Part IV of IV)

Analysts often apply the cost approach to value special-purpose property. And the measurement of economic obsolescence is an important but often controversial procedure in such cost approach analyses. Part one of this four-part series considered economic obsolescence concepts. Part two discussed the generally accepted measurement methods. Part three recommended responses to the most typical assessment authority objections to economic obsolescence measurements. This fourth part recommends best practices responses to other (but still common) assessor objections to economic obsolescence measurements.

Introduction

Valuation analysis (“analysts”) are often asked to value special-purpose industrial and commercial property. When analysts value such complex and integrated property collectively as a single operating unit, they often apply what is called the unit principle of property appraisal. Such appraisals are often developed for state and local property tax appeal and litigation purposes.

Analysts often apply the cost approach to value special-purpose property. And the measurement of economic obsolescence is an important but often controversial procedure in such cost approach analyses. Part one of this four-part series considered economic obsolescence concepts. Part two discussed the generally accepted measurement methods. Part three recommended responses to the most typical assessment authority objections to economic obsolescence measurements. This fourth part recommends best practices responses to other (but still common) assessor objections to economic obsolescence measurements.

Other Assessor Objections to Economic Obsolescence Measurements

This discussion summarizes other typical assessment authority objections to economic obsolescence measurements written in the context of property tax assessment appeal. These assessor objections are not quite as common as the assessor objections considered previously in this series. However, these objections are still raised often. And analysts (and taxpayer property owners) should be aware that there are also best practices responses to these assessor objections. Exhibit 1 presents a list of these other assessor objections to economic obsolescence measurements. Each of these other assessor objections are described (and responded to) below:

Exhibit 1: Other Typical Assessor Objections to Economic Obsolescence Measurements

- The economic obsolescence measurement can change materially from year to year

- If there was economic obsolescence, the taxpayer should record a GAAP accounting impairment charge

- If there was economic obsolescence, the taxpayer should disclose that fact to shareholders/others

- The analyst cannot subtract economic obsolescence in a historical cost less depreciation (HCLD) method analysis

- There can be no economic obsolescence if the unit or the industry market value/book value ratio exceeds one

- The analyst double-counted functional obsolescence and economic obsolescence

- Industry-wide economic obsolescence should not result in a taxpayer-specific value adjustment

- Economic obsolescence is temporary—or cyclical

- Investors expect economic obsolescence in certain industries so the appraisal should not adjust for that factor

- Investors expect the taxpayer unit to underperform; therefore, the appraisal should not adjust for economic obsolescence

Objection 11: Economic Obsolescence Measurements Change Materially over Time

Assessor Objection

The economic obsolescence measurement can change materially from one year to the next year.

Best Practices Response

The statement included in this objection is correct. Property values—including unit property values—can change from year to year. Most unit principle appraisals involve income-producing, special-purpose properties. The income generated by the taxpayer unit may change from year to year, so the unit’s actual economic returns may fluctuate over time. Economic and capital market conditions may also change from year to year. Therefore, the unit’s required economic returns may fluctuate over time. The difference between the taxpayer unit’s actual returns and the market participants’ required returns may change from year to year. Therefore, the unit-level economic obsolescence may fluctuate over time.

Assessment authorities are accustomed to fluctuations in property values due to economic obsolescence. For example, residential property values change (inversely) over time due to changes in mortgage interest rates. Like homeowners, unit property owners may decide not to sell their property during the periods when property values are depressed. However, the owner’s decision not to sell the property does not invalidate the fact that the property value (whether residential property or unit property) is depressed.

The objective of the unit principle appraisal (or of any appraisal) is to estimate a current value—and not a constant value over time.

Objection 12: There is No Economic Obsolescence without a GAAP Impairment Charge

Assessor Objection

If the property experienced economic obsolescence, then the taxpayer would have to record an impairment charge “write-down” on its generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) basis financial statements.

Best Practices Response

There are very specific accounting tests required for determining the impairment of a long-lived asset under U.S. GAAP. The guidance for such an asset impairment is provided by Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) topic 360, Property, Plant, and Equipment. Specifically, the asset impairment accounting guidance is provided in ASC topic 360-10, Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets. ASC topic 360-10 provides for a very specific quantitative test for an asset impairment:

- If the sum of future cash flow over the asset’s remaining useful life equals or exceeds the asset’s net book value (NBV), then an asset impairment is not permitted.

- If the sum of the future cash flow over the asset’s remaining life is less than the asset’s NBV, then an asset impairment is required.

The taxpayer cannot elect to take an asset impairment charge under U.S. GAAP. Either an asset impairment is required by ASC topic 360 or it is prohibited by ASC topic 360. There is no provision in ASC topic 360-10, or in any other U.S. GAAP, for any consideration of economic obsolescence. To illustrate the application of ASC topic 360-10, let’s consider an example. Our ASC topic 360-10 illustrative assumptions are as follows:

- Property NBV = $10,000,000

- Property remaining useful life = 10 years

- Property annual cash flow = $1,000,000

The ASC topic 360-10 long-lived asset impairment test would be developed as follows:

- Sum of cash flow over the asset’s remaining useful life – $10,000,000

- Property NBV – $10,000,000

- Conclusion: An asset impairment is not allowed

- Property’s actual internal rate of return (i.e., return on investment over the property’s remaining useful life) – 0%

Now, let’s consider the economic obsolescence implications of the same data set. Any positive market-derived required return on investment percent compared to a 0 percent property actual internal rate of return would indicate a substantial amount of property economic obsolescence. Under the provisions of ASC topic 360-10, an asset impairment is not allowed until the property’s actual internal rate of return is negative (not less than the property’s required rate of return—but actually negative).

Let’s consider the fundamental conceptual differences between (1) an economic obsolescence measurement and (2) the GAAP asset impairment test. The economic obsolescence benchmark is (1) a market-required rate of return compared to (2) the incomplete (pre-economic obsolescence) cost approach metric. In contrast, the asset impairment benchmark is (1) the undiscounted cash flow generated by the asset compared to (2) the NBV of the asset.

Analysts appreciate that the ASC topic 360-10 asset impairment test is intended to be extremely difficult to “fail.” This GAAP asset impairment test is intended to be difficult to “fail” for the following reasons:

- An asset impairment is permanent

- An asset impairment (or “write-down”) cannot be reversed

- An impaired asset value cannot be “written up” when the taxpayer property economic conditions improve

In contrast to the GAAP asset impairment test, a unit-level value will increase in the future when the unit’s economic conditions improve (and the taxpayer unit’s economic obsolescence decreases). It is important for the analyst and the taxpayer to understand that there is absolutely no relationship between (1) the ASC topic 360-10 asset impairment accounting and (2) the recognition of economic obsolescence in a cost approach property appraisal. And there is also no provision in ASC topic 360-10 for the asset owner to explain any of the reasons for—or any of the causes of—an asset impairment.

Objection 13: The Taxpayer Should Make a Public Disclosure of Economic Obsolescence

Assessor Objection

If the unit really experienced economic obsolescence, then the taxpayer property owner would have to publicly disclose that obsolescence.

Best Practices Response

There is no FASB U.S. GAAP requirement to disclose economic obsolescence. There is no International Accounting Standards Board international (or IFRS) GAAP requirement to disclose economic obsolescence. There is no Securities and Exchange Commission requirement to disclose economic obsolescence. There is no New York Stock Exchange requirement to disclose economic obsolescence. There is no Nasdaq requirement to disclose economic obsolescence. There is no Internal Revenue Service requirement to disclose economic obsolescence.

There is simply no requirement for a property owner to disclose the existence of unit-level economic obsolescence to anyone.

Objection 14: The Analyst Cannot “Subtract” Economic Obsolescence from HCLD

Assessor Objection

It is not appropriate for an analyst to “subtract” economic obsolescence in a historical cost less depreciation (HCLD) method cost approach analysis.

Best Practices Response

First, economic obsolescence is not a “subtraction” from any cost measurement. Like all other types of appraisal depreciation, economic obsolescence is an adjustment from a cost metric that is applied in order to conclude a value.

Second, the cost approach HCLD method is not the same as accounting net book value. It is a correct statement that a GAAP accounting net book value figure does not recognize the existence of unit-level economic obsolescence. Rather, accounting NBV only considers accounting depreciation. In contrast to accounting NBV, the HCLD method is based on (1) the unit-level historical cost (or original cost, if available) less (2) all forms of appraisal depreciation. In any cost approach analysis, appraisal depreciation includes the following three components:

- Physical deterioration

- Functional obsolescence

- External obsolescence (including economic obsolescence)

Typically, total appraisal depreciation does not equal total accounting depreciation. This is because accounting depreciation is intended to systematically allocate the cost of a property investment over the expected useful economic life of the property. Typically, accounting depreciation is not intended to indicate or even approximate a current market value for a property.

Some regulated industry entities have to apply regulatory accounting principles (including what are often called regulatory depreciation principles) for certain compliance purposes. These regulated industry entities can elect to apply regulatory accounting principles as their GAAP accounting principles under the provisions of FASB ASC topic 980, Regulated Operations. In such instances, the regulatory accounting depreciation becomes the financial accounting depreciation for those regulated entities.

The HCLD method is summarized as follows:

Historical cost

– Appraisal (including regulatory) depreciation

= Value indication

That is, the HCLD method is NOT summarized as follows:

Historical cost

– Financial accounting depreciation

= Value indication

There is no generally accepted valuation professional organization (VPO) literature, appraisal standard, appraisal credentialing course, or other professional appraisal guidance that states that economic obsolescence should not be considered in the HCLD method.

Objection 15: There Can be No Economic Obsolescence if the Market Value/Book Value Ratio Exceeds One

Assessor Objection

The only appropriate test for economic obsolescence is the so-called market value/book value (MV/BV) ratio. If that ratio exceeds 1, then there is no unit-level economic obsolescence.

Best Practices Response

Some assessors calculate a MV/BV ratio based on the taxpayer stockholders’ equity only. Some assessors calculate a MV/BV ratio based on the taxpayer total invested capital (i.e., long-term debt plus stockholders’ equity). In either case, the data that these assessors use to calculate the MV/BV ratio are extracted from guideline publicly traded companies. This MV/BV ratio comparison assumes that all market value—and any market value price premium over book value—relates entirely to the tangible property recorded on the company’s GAAP balance sheet. However, there are numerous reasons why a company’s market value of equity (or of total invested capital) can be greater than the company’s book value of tangible property.

In addition to the value of real estate and tangible personal property, a company’s market value of equity (or of total invested capital) encompasses the value of the following:

- Working capital accounts

- Identifiable intangible assets

- Intangible value in the nature of goodwill

- Present value of growth opportunities

- Intangible investment (public security) attributes

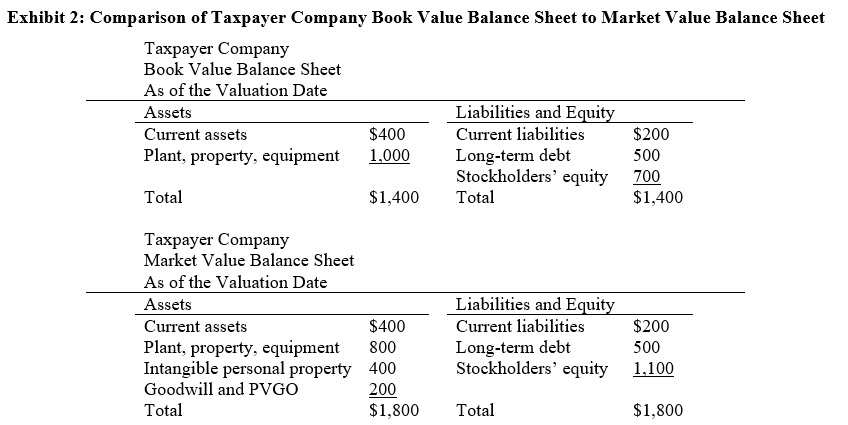

The meaningless (from a property appraisal perspective) nature of the MV/BV ratio comparison is illustrated by the example presented in Exhibit 2.

This example considers an illustrative public company taxpayer. This example assumes that both the book value and the market value of the company’s long-term debt is $500. This example assumes that the book value of the stockholders’ equity is $700 and that the market value of the stockholders’ equity (based on the public stock price) is $1,100. This hypothetical company’s MV/BV ratio is analyzed in the following calculations:

- MV/BV ratio based on TIC (i.e., the LTD & the SE) = 1.3x

- ($1,600 ÷ $1,200) = 1.3x

- MV/BV ratio based on stockholders’ equity only = 1.7x

- ($1,100 ÷ $700) = 1.7x

Let’s assume the analyst conducted a fair market value valuation of all of the company’s tangible assets and intangible assets in order to allocate the market value of invested capital. This fair market value appraisal is the basis for the Taxpayer Company Exhibit 2 market value balance sheet. In contrast to the incorrect conclusion implied by the above MV/BV ratio calculations, the actual unit-level economic obsolescence implied by the Exhibit 2 example is presented below:

Book value of the plant, property, equipment (only) $1,000

– Market value of the plant, property, equipment 800

= Market value decrement (below book value) in plant, property, and equipment $200

= Implied economic obsolescence percentage 20%

(i.e., $200 ÷ $1,000)

The above example illustrates that the taxpayer company (or the taxpayer industry) MV/BV ratio is a meaningless measure of unit-level economic obsolescence. This ratio is meaningless because the MV/BV ratio ignores all of the other influences on the market value of a company’s securities—other than the value of the company’s tangible property.

Objection 16: The Analyst Double-Counted Functional Obsolescence and Economic Obsolescence

Assessor Objection

The unit-level economic obsolescence measurement is already captured in the functional obsolescence adjustment.

Best Practices Response

Functional obsolescence and economic obsolescence are two different types of cost approach adjustments. However, both types of obsolescence adjustments may be influenced by these two conditions:

- The property is earning less income than its benchmark level of profit or return

- The property has too much investment compared to its benchmark level

Functional obsolescence is caused by factors internal to the taxpayer property, including inadequacy and superadequacy. Functional obsolescence is caused by factors directly associated with the unit’s tangible property, including the following:

- Changes in technology (e.g., a new property is more efficient)

- Changes in construction or component material (e.g., a new property would be made from different material)

- Changes in size (e.g., too much or too little)

- Changes in location (e.g., too close or too far away)

Functional obsolescence is often measured by reference to:

- capitalized excess operating expenses (compared to a benchmark property) and

- excess capital costs (compared to a benchmark property).

Functional obsolescence is sometimes curable. For example, the ideal replacement property would be smaller (or larger), be made of different material, have a different fuel or raw material source, have a different layout or configuration, and have more efficient equipment or amenities. Some functional obsolescence is not curable. For example, there may be physical constraints that prohibit the construction and operation of the ideal replacement property.

Economic obsolescence is caused by factors that are external to the unit’s tangible property, including the following:

- Actions of competition

- Consumer demand and preferences

- Changes in the price of material, labor, and overhead

- Weather and climate changes

- Government and regulatory actions

- Capital market returns and interest rates

- Taxpayer responses to the above factors

Therefore, economic obsolescence is generally considered to be incurable. Analysts should be careful to distinguish between (1) value decrements caused by functional obsolescence (internal factors) and (2) value decrements caused by economic obsolescence (external factors). For example, let’s assume that an electric generation plant experiences excess fuel costs (compared to a benchmark level). The analyst should consider the following:

- Are the excess fuel costs caused by excess fuel consumption due to an inefficient heat rate (i.e., fuel consumed per kilowatt of electricity produced) compared to a modern plant—that is, due to functional obsolescence?

- Or, are the excess fuel costs caused by increased natural gas prices that are due to general industry conditions or an unfavorable supply contract—that is, due to economic obsolescence?

The analyst should be careful to not consider the same cause of excess operating expenses (low-income metric) and excess capital costs (high investment metric) in both the functional obsolescence measurement and the economic obsolescence measurement.

Objection 17: Industry-Wide Economic Obsolescence Should Not Result in a Taxpayer-Specific Value Adjustment

Assessor Objection

If there is industry-wide economic obsolescence, then industry participants expect lower returns and the unit value should not be adjusted.

Best Practices Response

If the economic obsolescence is industry-wide (e.g., decreased prices for goods or services produced, increased prices for raw materials consumed), then every industry property owner is experiencing some amount of economic obsolescence. Economic obsolescence is measured as the difference between:

- the property inadequate return on investment and

- the industry inadequate return on investment.

The industry’s (and the property’s) required return on investment is measured without (or before) the adjustment for economic obsolescence. If there is industry-wide economic obsolescence, then investors will adjust downward the prices for all industry properties until the investors are earning their required rate of return. Assessors are accustomed to dealing with industry-wide economic obsolescence. When mortgage interest rates increase nationwide, then all residential property values typically decrease. Assessors cannot disregard this general residential property value decrease simply because it is affecting all residential real estate.

Objection 18: Economic Obsolescence is Temporary—or Cyclical

Assessor Objection

If it exists, economic obsolescence is temporary—or cyclical. It will resolve itself over time when the industry cycle turns up.

Best Practices Response

The economic obsolescence measurement may, in fact, be temporary or cyclical. The economic obsolescence measurement may increase or decrease materially from year to year based on:

- changes in the unit’s actual financial performance over time and

- changes in the market participants’ required return on investment over time.

This cyclical nature of the measurement is further proof of the fact that economic obsolescence is external to the taxpayer’s property. However, in periods when economic obsolescence exists, it affects the property value. During those periods, the property value decreases, and that value decrease should be reflected in the property tax assessment.

Also, in periods when economic obsolescence does not exist, it does not affect (or it little affects) the property value. During those periods, the property value does not decrease, and that fulsome value should be reflected in the property tax assessment. Typically, property owner/taxpayers do not appeal the unit property assessment during periods when there is little or no economic obsolescence. Accordingly, the assessment authority should recognize an appropriate property value adjustment during periods when there is a material amount of economic obsolescence.

Assessment authorities experience the cyclical nature of economic obsolescence in residential real estate assessments. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic caused home prices to increase for several years. The impact of increased mortgage interest rates has caused home prices to decrease recently. The same type of cyclical external factors that affect the value of residential property also affects the value of industrial and commercial property—sometimes to an even greater degree.

Objection 19: Investors Expect Economic Obsolescence in Certain Industries so the Appraisal Should Not Adjust for that Factor

Assessor Objection

Due to regulatory lag or historical taxpayer industry performance, investors expect low rates of return. Therefore, the unit appraisal should not adjust for such below-market-expectations economic obsolescence.

Best Practices Response

The benchmarks applied in economic obsolescence measurements should be based on market-derived, empirical data. These benchmarks may be prices, volumes, costs, profit margins, returns on investment, and other metrics. The empirical data considered in the measurement may relate to guideline public companies, trade association and other industry sources, the taxpayer unit’s historical results of operations, the taxpayer unit’s cost of capital, and other market participant sources. The point is, the benchmarks applied in economic obsolescence measurements are metrics that investors expect. This is because they are metrics that investors can achieve. This benchmark represents the opportunity returns available to market participant investors.

The market participant investors will either (1) invest in the benchmark investments—and earn the opportunity rate of return—or (2) invest in the taxpayer unit—at a price that will allow them to still earn the opportunity rate of return. If the market participants invest in the taxpayer unit, they will only do so at a price that will yield to them the otherwise available opportunity rate of return. The difference between that price (i.e., a price that yields the opportunity return) and the unit’s cost metric is called economic obsolescence.

So, if industry returns are consistently low, then market participants incorporate those low returns into their assessment of opportunity returns. But if some industry participants (e.g., guideline public companies or industry competitors) are earning higher returns, then market participants will incorporate those higher returns into their assessment of opportunity returns. Therefore, the benchmark returns (and the opportunity returns) will be influenced by regulatory lag or by any other external factors causing the economic obsolescence.

If the taxpayer unit’s returns are less than the benchmark (or opportunity) returns, the appraisal does have to adjust the cost approach for economic obsolescence. All investor expectations are fully incorporated into the benchmark (or opportunity) rates of return. If the taxpayer unit cannot generate that benchmark rate of return, then the market participants will reduce the bid price (i.e., the value) of the subject unit until the unit price yields that benchmark (or opportunity) return on investment.

Objection 20: Investors Expect the Taxpayer Unit to Underperform, so the Appraisal Should Not Adjust for Economic Obsolescence

Assessor Objection

The taxpayer unit consistently underperforms the benchmark financial or operational metrics. Investors expect the unit to underperform. Therefore, the appraisal should not account for economic obsolescence.

Best Practices Response

The taxpayer unit may have underperformed the benchmark financial or operational metrics for the last five years. The taxpayer unit may be expected to underperform the benchmark financial or operational metrics for the next five years. These facts do not indicate that there is no economic obsolescence associated with the taxpayer unit. Instead, these facts actually indicate that there is consistent economic obsolescence at the taxpayer unit.

For example, if the unit consistently does not earn its cost of capital, that fact does not imply that the cost of capital is too high. Rather, that fact does imply that the unit’s actual return on investment is too low—and should be reflected in an economic obsolescence measurement.

Market participants look to the market for their opportunity to benchmark metrics. Market participants can earn those market-derived opportunity returns elsewhere. So, market participants also expect to earn those market-derived opportunity returns at the taxpayer unit. If the taxpayer unit consistently underperforms the required metrics, market participants will bid down the price of the taxpayer unit. Market participants will continue to bid down the unit price until the participants can earn the opportunity rate of return on an investment in the taxpayer unit. This “bid down” price becomes the value of the taxpayer unit. And the difference between the unit’s market value and the unit’s cost metric is called economic obsolescence.

If the taxpayer unit consistently underperforms the market’s required return on investment metric, then the unit will consistently experience economic obsolescence. The market’s required return on investment becomes the unit’s cost of capital (or required rate of return). That market-derived cost of capital is not reduced because of the unit’s historical (or expected) underperformance.

Summary and Conclusion

This discussion is the final of a four-part series with regard to the application of the cost approach within a unit principle appraisal of a taxpayer company’s industrial and commercial property. This series focused on the measurement of economic obsolescence within the appraisal of such complex special-purpose property for property tax appeal purposes.

A unit principle appraisal is different from a summation principle appraisal. A unit principle property appraisal is different from a business appraisal. Cost (however measured) does not equal property value. Rather, cost (however measured) minus all types of appraisal depreciation indicates property value. Economic obsolescence is not a “subtraction” from the cost approach value. Rather, economic obsolescence is an “adjustment” that is necessary to get to the cost approach value.

The measurement of economic obsolescence typically does consider some taxpayer income-related metrics. However, that consideration does not convert the cost approach into the income approach. It is noteworthy that the market approach also considers taxpayer income-related metrics. Economic obsolescence is typically measured on a comparative basis. Unit-level economic obsolescence measurements typically compare the unit-level economic condition of “what you have” to the unit-level economic condition of “what you want.” The unit-level economic condition you “want” does not mean the economic condition that the taxpayer desires or would like to have. Rather, the unit-level economic condition you “want” means the economic returns that market participants “require” to induce them to invest in the taxpayer unit.

The benchmarks for economic obsolescence measurements are market-derived empirical returns that are earned by guideline companies, other industry participants, or the taxpayer unit (historically). The benchmark returns considered in the economic obsolescence measurement are the opportunity returns available to investors or market participants in the taxpayer’s industry.

The Capitalization of Lost Income Method (CILM) is one generally accepted economic obsolescence measurement method. The CILM is not the income shortfall method. And the CILM is not the income approach.

There is typically not one industry-wide measure of economic obsolescence. And there is typically not one taxpayer company measure of economic obsolescence. Rather, economic obsolescence is applied within the context of each individual unit-level cost approach analysis. That is, the economic obsolescence measurement is specific to the appraisal cost metric. For example, a unit appraisal based on a $10 million property cost metric will have a different economic obsolescence adjustment than an appraisal of the same unit that is based on a $50 million property cost metric. In other words, the greater the property cost metric, the lower the cost-based unit-level return on investment—and the greater the unit-level economic obsolescence adjustment.

Analysts should be aware that there are best practices responses to address the typical assessment authority objections related to economic obsolescence measurements. Assessors often express these objections to economic obsolescence analyses developed within the unit principle appraisal of taxpayer industrial and commercial property.

The opinions and materials contained herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the author’s employer. In authoring this discussion, neither the author nor Willamette Management Associates, a Citizens Company, is undertaking to provide any legal, accounting or tax advice in connection with this discussion. Any party receiving this discussion must rely on its own legal counsel, accountants, and other similar expert advisors for legal, accounting, tax, and other similar advice relating to the subject matter of this discussion.

Robert Reilly, CPA, ASA, ABV, CVA, CFF, CMA, is a Managing Director in the Chicago office of Willamette Management Associates, a Citizens company. His practice includes valuation analysis, damages analysis, and transfer price analysis.

Mr. Reilly has performed the following types of valuation and economic analyses: economic event analyses, merger and acquisition valuations, divestiture and spin-off valuations, solvency and insolvency analyses, fairness and adequacy opinions, reasonably equivalent value analyses, ESOP formation and adequate consideration analyses, private inurement/excess benefit/intermediate sanctions opinions, acquisition purchase accounting allocations, reasonableness of compensation analyses, restructuring and reorganization analyses, tangible property/intangible property intercompany transfer price analyses, and lost profits/reasonable royalty/cost to cure economic damages analyses.

Mr. Reilly has prepared these valuation and economic analyses for the following purposes: transaction pricing and structuring (merger, acquisition, liquidation, and divestiture); taxation planning and compliance (federal income, gift, estate, and generation-skipping tax; state and local property tax; transfer tax); financing securitization and collateralization; employee corporate ownership (ESOP employer stock transaction and compliance valuations); forensic analysis and dispute resolution; strategic planning and management information; bankruptcy and reorganization (recapitalization, reorganization, restructuring); financial accounting and public reporting; and regulatory compliance and corporate governance.

Mr. Reilly can be contacted at (773) 399-4318 or by e-mail to RFReilly@Willamette.com.