A Contrarian View to Discount for Lack of Control

The “Least Bad” Method

Determining a discount for lack of control (DLOC) is one of the more challenging tasks facing business valuators. The reason for this is the methodologies used each have weaknesses. In this article, David Goodman looks at two methods and explains the difficulties in relying on them. This is a case where business appraisers may need to rely on the “least bad” method … a term of art.

Determining a discount for lack of control (DLOC) is one of the more challenging tasks facing business valuators. The reason for this is the methodologies used each have weaknesses. In this article, I am going to look at two methods and explain the difficulties in relying on them. This is a case where the business appraiser community may need to rely on the “least bad” method … a term of art.

Mergerstat Review

FactSet Mergerstat publishes annually data on transactions involving at least 5 percent of a company’s stock. One of the statistics included is the premium paid by an acquiring company for the acquired company’s stock. This is considered a control premium. Algebraically, this control premium is converted into what is purported to be a discount for lack of control (minority interest discount).

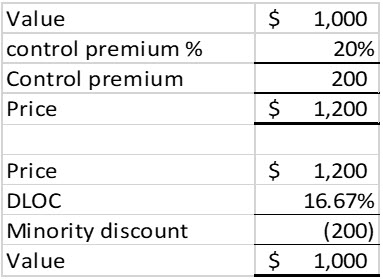

The formula to do this is: DLOC = 1-(1/(1+CP), where CP is the control premium.

The following shows how this works.

There are two problems with this methodology: one is the implied assumption behind the methodology and the second is with the data itself.

If I pay a 20 percent premium to purchase a company, why would I give up control for the inverse of that? Elmer Fudd owns 51 percent of Carrot Enterprises, Inc. Bugs Bunny owns the other 49 percent. Bugs is a pesky shareholder; always wanting more carrots distributed to him than Elmer wants to distribute. Elmer buys Bugs out for a 20 percent premium over the value of the stock. Problem solved. Now that Elmer has control of Carrot Enterprises, why would he surrender control at a discount? If anything, Elmer would want a premium for having to put up with the pesky minority shareholder.

Now let’s look at this from the buyer’s perspective. Elmer owns 100 percent of Carrot Enterprises. He wants to give 5 percent to each of his four kids. A value needs to be established for the 5 percent interest. Treasury Regulation Section 20.2031-1(b) defines fair market value as “the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.” The International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms expands this definition to reflect that the buyer and seller are hypothetical buyer and sellers.

The question then is what is the willing hypothetical buyer willing to pay for a 5 percent interest in Carrot Enterprises? A 5 percent shareholder will have none of the benefits of control, cannot be assured of any distribution, and may face a limited market for the stock should and if they can sell their interest. The reality is most of us would not be willing to purchase this 5 percent interest, and if we did, the discount would be much greater than the 16.67 percent discount calculated algebraically as the inverse of the control premium.

The second issue with the Mergerstat data is the data itself. The transactions listed are most likely strategic or synergistic transactions. The acquiring companies were likely looking to purchase market share, eliminate a competitor, purchase intellectual capital, and so forth. The selling companies may or may not have been under compulsion to sell. These are likely not fair market value transactions. Further, these transactions occur in a different universe than the typical small companies we value.

Another method is to look at the cashflow to the minority shareholder.

Cashflow to the Minority Shareholder

When valuing a control interest using the income approach, we may make normalization adjustments. However, a minority shareholder may have no control over what they receive from the company. In this case, an argument can be made that no adjustment should be made to the cashflow to the minority shareholder.

One criticism of not making normalization adjustments is that if publicly traded stock data is used for the discount rate, then there is a mismatch between the numerator (cash flow) and denominator (discount/capitalization) rate. (See writings of Chris Mercer.) Because of this, normalization adjustments need to be made. The result is a marketable interest that is neither control nor lack of control. The valuation analyst must then determine a discount for lack of marketability (which includes any implied discount for lack of control). The discount may be based on the liquidation horizon to the shareholder. But what if the minority shareholder does not receive dividends or only receives a dividend to cover their income taxes on the pass-through earnings? What if the liquidation horizon is indefinite?

A solution to this dilemma may be found by returning to the fundamental principles of economic value which apply to all business valuations.

Ray Miles (founder of the Institute of Business Appraisers) discusses in Basic Business Appraisal, 1984, three principles of economic value. These principles apply to all business valuations.

The first is the Principle of Alternatives. “The Principle of Alternatives states that: in any contemplated transaction, each party has alternatives to consummating the transaction.”

A buyer has options on how to invest their money and a seller is not under any compulsion to have to sell their business. They can choose to keep investing in their business.

The second principle of economic value is the Principle of Substitution. The Principle of Substitution states that: “the value of a thing tends to be determined by the value of acquiring an equally desirable substitute.” When valuing a small business, we need to consider what will make this investment an equally desirable substitute. If we invest in a publicly traded portfolio, we will have an expectation of a certain return over time. For the small business, we generally will expect a significantly higher return than the publicly traded portfolio to account for the increased risk of the small business.

The third principle of economic value is the Principle of Future Benefits. The Principle of Future Benefits states that: “economic value reflects anticipated future benefits.”

Let’s look at how these principles of economic value apply to the income approach using the capitalization of earnings or discounted period cash flows methods.

When we use publicly traded stock data in the build-up method to derive our discount/capitalization rate, we are applying the principle of alternatives. Our alternative to purchasing the minority interest is to invest in a publicly traded stock portfolio.

Our cash flow represents the potential future benefits. If we are the minority shareholder, the cash flow we receive may be the best indicator of the potential future benefits.

Finally, we need to make an investment in our subject company an equally desirable substitute to an investment in our hypothetical publicly traded portfolio. This is why for small businesses we add a company specific risk premium.

The advantage of this methodology is that it avoids having to specifically identify a discount for lack of control. The value of the minority interest is the present value of the expected future earnings plus a liquidation value.

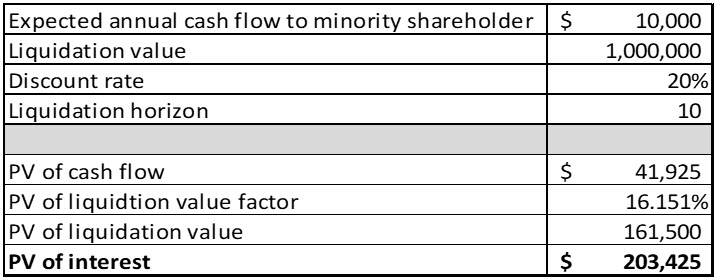

The following shows how this might work. The annual cash flow is $10,000 after-tax and the after-tax liquidation value in 10 years is estimated to be $161,500. The capitalization rate is 20 percent. For the purpose of this example, the capitalization rate and discount rate are assumed to be the same.

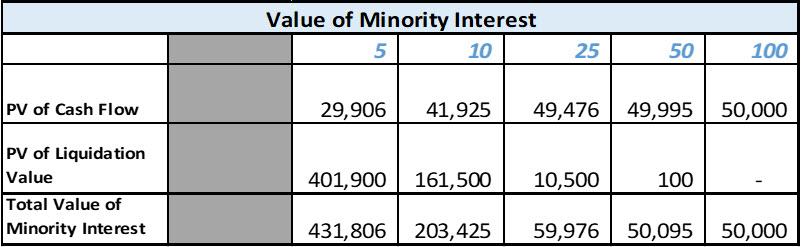

The following table shows how the liquidation value disappears as the liquidation horizon increases.

For a minority interest for which the after-tax value is $0 and the liquidation horizon is indefinite, the value of the minority interest is basically $0.

In this example, I have assumed the discount rate is the same for the cash flows and the liquidation value. But is this the case? Should the discount rates be different? Basically, I am being asked to invest a fixed amount of money in an investment for some period of time. The rate of return needs to be based on the risk that the value will be there at the end of the holding period. Think about how we apply the income approach using discounted cash flows. We discount period cash flows, and then calculate a terminal value which is discounted back to its present value using the discount rate. (The terminal value may be determined using capitalization of earnings or some liquidation value.)

However, this approach is not without its difficulties. The biggest one is determining the liquidation value. First, if the liquidation horizon is indefinite, then we may not need to value the liquidation value. Notice how quickly the value drops from a 10-year horizon to a 25-year horizon. Otherwise, we must value the company with normalization adjustments and use discounted cash flows or capitalization of earnings to determine the present value of the company. The present value of the entire company times the ownership percent represents the present value of the liquidation value.

What the liquidation value is and the expected holding period will be fact specific. Some things to consider:

- Is there a stock buy-back agreement?

- Is the intent for the company to be multi-generational?

- Is the company positioning itself to be acquired?

- Is there an expectation that the company will make a public offering?

- Is the company financed by angel investment or venture capital?

In summary, using Mergerstat data does not apply to most of the small businesses we value. The assumption behind converting a control premium to a minority interest discount is also flawed. While imperfect, discounting the cash flows to the minority shareholder seems to be the best solution.

David Goodman, MBA, CPA, CVA, has 25 years of experience in performing business valuations and forensic accounting services for family law and business disputes. He also has prepared business valuations for tax and buy-sell purposes. He has an MBA from the Amos Tuck School at Dartmouth College. He is a past-president of the NACVA-Mass State Chapter, past chair of the Massachusetts Society of Certified Public Accountants Litigation and BV committee, and a past board member and treasurer of the Massachusetts Collaborative Law Council. As a financial neutral, Mr. Goodman has helped divorcing couples reach peaceful equitable solutions. He has presented on business valuation and tax issues related to divorce at NACVA annual conference, NACVA-Mass. State Chapter, and the Massachusetts Collaborative Law Council. He has also testified as an expert witness in court and arbitration. He is currently serving on the editorial board of QuickRead.

Mr. Goodman can be contacted at (617) 698-3950 or by e-mail to dgoodman@joacpa.com.