What is Your Privacy Fine Exposure?

From $600 to Over $1 Billion

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and other data protection regulations apply to the smallest sole practitioner firm among us to the largest and each must take steps to implement a cybersecurity plan, to follow it, and to respond when an incident occurs. The failure to provide protection can result in fines. In this article, the author describes why Amazon and Google were fined under the EU’s GDPR.

For the past five years, organizations have been dodging and weaving the myriad data protection regulations spawned from the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Introduced in 2016, taking effect in 2018, and mimicked by other countries and states since, data privacy regulations have attempted to force a reckoning for companies that gather, store, share (lawfully or not), and use a consumer’s data. While millions are affected by identity theft resulting from data breaches, the affected consumer has not been (and will not be in the foreseeable future) compensated in a manner commensurate with their loss.

The previous 2021 update of GDPR fines and fees encouraged users to be diligent in their opting out of trackers and cookies. Such an action is tedious, at best, and completely useless at worst. About $240,000,000 in fines were levied against Google and Amazon for tracking customers without their consent (i.e., using those cookies even if a user had opted out) and providing a defective opposition mechanism (i.e., making the cookie opt-out process absurdly non-navigable). For instance, many cookie pop-ups display toggle switches to the user to indicate consent or the lack thereof, but the clever (or asinine) website design fails to indicate which direction is “yes” and which direction is “no”.

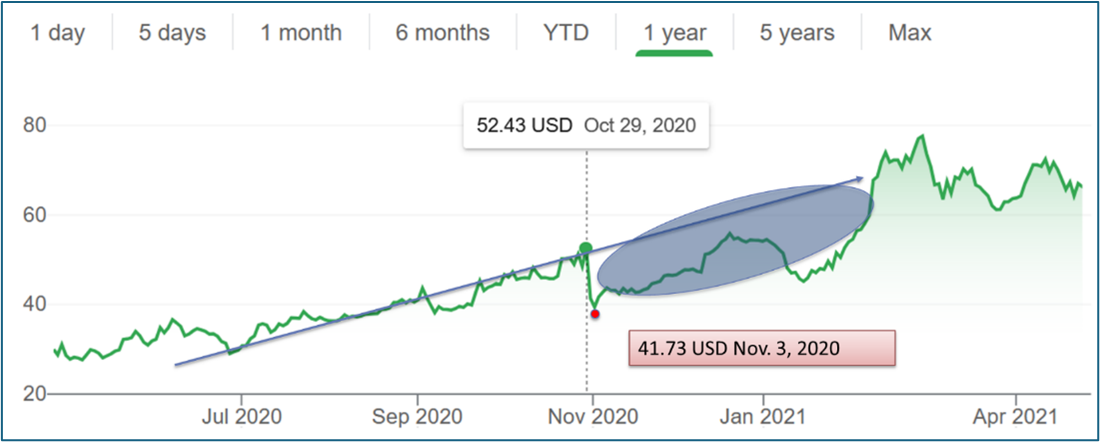

A record fine of nearly $1 billion was levied against Amazon related to its targeted advertising practices in June 2021; that is in addition to the $120 million fine levied against it in 2020 for gathering data using cookies without consent. Figure 1 shows a chart of Amazon’s share price on Dec. 31, 2020, after the initial fine was levied.

Figure 1: Amazon Share Price, https://www.google.com/finance/quote/AMZN:NASDAQ?window=5Y

Figure 1: Amazon Share Price, https://www.google.com/finance/quote/AMZN:NASDAQ?window=5Y

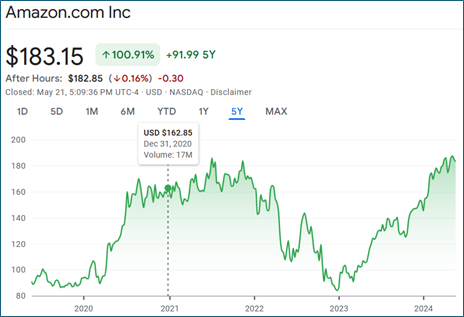

Figure 2 shows Amazon’s share price on July 09, 2021, after the 2021 fine, which was the largest levied under GDPR at the time, was announced. On its face, the share price does not indicate a significant change in share price as a result of these fines. Perhaps that concern is built in at a different time, such as earlier when an investigation is first launched, or later when an appeal determination is made.[1]

Figure 2: Amazon Share Price, https://www.google.com/finance/quote/AMZN:NASDAQ?window=5Y

Figure 2: Amazon Share Price, https://www.google.com/finance/quote/AMZN:NASDAQ?window=5Y

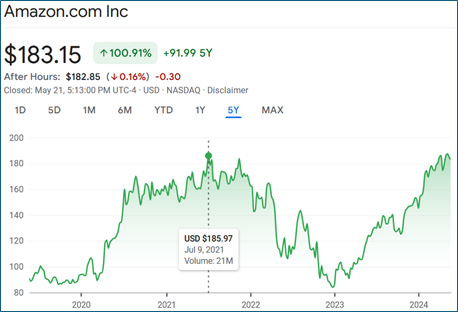

The complete lack of a visible share price effect for Amazon contrasts starkly against the share price effect of Twitter, when accounts were hacked in 2020. Figure 3 shows an initial drop in Twitter’s share price between October 29 and November 03, 2020.

The drop in share price is not the only value here; as many readers know, the trajectory of a company’s expected profits may also indicate a larger portion of loss, indicated in the shaded area of Figure 4. The blue line represents a simplistic trajectory over the green line of actual share prices. The shaded area represents the difference between what could have been and what was. [2] The speed of the drop and the timeline for recovery may also provide insight into investors’ cybercrime perception.

Figure 4: Slide from author’s presentation, Valuing Loss in Cybercrime Engagements

What does this mean about investors’ perception of cybercrime incidents? Do investors care about cybercrime, or a corporation’s role in perpetrating it?[3] Do investors consider cybercrime as a normal course of business these days and care only when famous public accounts are impacted (or when people do not get the doubled bitcoin those famous accounts promised as part of the Twitter incident)? What factors drive share prices and how can a business determine whether an incident will cause a dip? Many other things were happening mid-2021 that may have buffered Amazon’s share price against a cybercrime-related dip.

We have seen the evolution of the good corporate citizen from the 1990s into corporations with citizen-like rights in the 2010s and finally into what we now call Environmental Social Governance (ESG), along with the UN’s 17 (count ‘em) goals for sustainable development. These ideologies drive impact investing where investors put their money where their proverbial mouths are and place funds with organizations that strive to meet some of these new “goodness” directives, regardless of profitability forecasts.[4] Do the “goodness” directives apply to cybercrime incidents, where fines are levied against companies who have a direct roll in the perpetration of that incident?[5]

Unfortunately, the answer is not really. Impact investing concepts do not appear to guide investors when large corporations are the subject of fines; investments do not appear to divest from cyber-inept companies such as Amazon, Google, Meta, Mariott, and other large corporations when they receive very high fines under GDPR. In fact, consumers do not appear to care either, as evidenced in their continued use of the products and services. Some impact divestiture can be seen with large energy companies who expend quite a lot of energy convincing their investors of their commitment to renewable energy or whatever the ESG demand of the day is; well, except for Exxon, who would prefer the fight.[6] Activist shareholders pushing an ESG agenda, from Exxon’s standpoint, appear to be a plague upon their duty to the rest of the shareholders. Other energy companies seek to placate investors with tales of their “goodness” and ESG goals. Sometimes, that works out and other times, the entire basis of claimed “goodness” collapses.[7]

Cybersecurity does not seem to play a role in ESG concerns; although a few have suggested it should. KPMG conducted a CEO Outlook survey in 2022 and concluded “ESG and cybersecurity are crucial for corporate success,” and noted, “While environmental aspects of the ESG agenda have received significant attention, other elements such as cybersecurity and privacy have not been as well-developed.”[8] KPMG’s marketing brochure identifies elements of cybersecurity within an ESG framework:

- Critical infrastructure and decarbonization are environmental considerations that depend on digital transformation and smart technology, where the anticipation of threats is necessary to ensure uptime.

- Data protection, ransomware, and threats to freedom of speech are all social considerations, and protecting consumer information fosters trust (and trust maintains your customer base).

- AI concerns, data ethics (i.e., racial bias and other bias creep in technology), and cyber literacy are also part of a corporation’s social responsibility.

- Data accuracy (i.e., delayed data breach reporting, greenwashing, and sustainability standards) are critical governance aspects that heavily rely on digital processes. Poor decisions get made when the underlying data is poor at the outset.

These are basic cyber hygiene issues, rooted in general online self-protection and are not indicative of the more robust cybersecurity frameworks generally pitched to large corporations. KPMG’s force-fitting of basic cyber hygiene into the framework of ESG does not address the balance that a public corporation must maintain between addressing these concerns and its bottom line (i.e., its responsibility to its shareholders). Does the corporation merge its data protection attorney with its carbon credit Chanticleer, and save on some salary expenses?

A small business owner, or even a mid-sized business board, may read this and think, what do I care? These big problems do not affect me. Ah, but they do. While very large fines levied under GDPR generally make the news more often, many smaller fines are levied against small and mid-sized firms, which may have much smaller profit margins or a much tighter operating budget. We cannot all have a hundred subsidiaries carry our debts separate from our assets.

The complete lack of concern illustrated in little to no share price effects and in ongoing consumer engagement when a cybercrime incident occurs does not translate to the small practitioner. Fines are not levied with the corporation’s gross revenue in mind.

Who Cares?

It is these smaller fines that are the biggest concern for financial practitioners; we operate in the realm of confidentiality and specific disclosure requirements.[9] Can your practice handle the fines related to unauthorized access to your system? Do you think your cloud server service provider will cover your expenses? Think again, because they will not.[10]

Google and Amazon are two of the largest cloud providers—and they have been hit with massive fines related to misuse of data. Does that shake your confidence in them enough for you to change your service provider? Probably not. And more importantly, can your firm float a $10,000 fine? A $30,000 fine? How about a $100,000 fine? How about a $100,000 fine related solely to your weak cybersecurity policy when you have not suffered a data breach or ransomware attack ever? It does not seem fair, and it is not. In fact, one of the most often heard complaints related to GDPR fines is the complete lack of consistency related to infractions and revenue.

A website about locating family has revenue of under $5,000,000 but was recently fined about 10 percent of that revenue for its failure to appoint an EU representative.[11] All of the fines levied against Google total 0.06 percent of its revenue.[12] Fines levied against Google are for failures in its actions; insufficient transparency and control over the processing of personal data, right-to-be-forgotten violations, defective opt-out tracker options, and obtaining data without consent. Google then sells that data to whoever is buying and still has little to zero incentive to stop any of its identified behavior; it loses 0.06 percent of its revenue in its sofa, probably. The old clichés, a drop in the bucket or a slap on the wrist, are vast overstatements for this scenario. Arguably, the costs for regulatory fines could be treated as an extremely minimal line item under costs of goods sold for large corporations.

Still, a very small business owner may read the above fine and think these concerns are still not applicable because he or she does not sell data. The smallest fine levied to date was 600 euros levied against a property owner’s association in Romania for its disclosure of personal data and its failure to cooperate.[13] This is not a data sale.

The first fine imposed by Belgium under GDPR was against a mayor for 2,000 euros.[14] A service provider to the mayor sent an e-mail and included her clients in the cc: field; the mayor later used those e-mails for sending election propaganda. This is not a data sale. Does your firm run e-mail marketing campaigns? How does your firm build its client list for such a campaign and did you appropriately gather consent from each e-mail recipient? Selling data is not a prerequisite to fines.

Once upon a time, I worked for a firm that harvested recipient e-mails from all users on its e-mail server and launched an e-mail marketing campaign using every e-mail it found. The firm received many complaints from former clients and from attorneys with whom years-long relationships had been built. It was a black eye for the otherwise professional firm and many relationships could not be recovered. The incident also occurred prior to GDPR and other data protection laws so the clients and attorneys had little recourse other than to take their business elsewhere. Today, those recipients would be able to file complaints for the (mis)use of their data without their (informed and explicit) consent. Nearly every state has a cause of action mechanism similar to GDPR if you are not affected by GDPR itself, but remember, GDPR applies to every organization that markets to a resident of the EU.

Do you run social media campaigns with the locations carefully selected to exclude residents? Probably not; many such marketing efforts are focused on keywords and click-through-rates to expand visibility, not limit it. Meet with your marketing person, team, or third-party firm to determine how they limit your advertising.

Action Items for Practitioners

I said it four years ago and I will say it again: get a cybersecurity plan in place now and follow it. It applies to you, the sole practitioner, and to every firm larger than that. There are free tools that are easy to use such as, https://assess.cyberhouston.org/. NIST provides a massive amount of resources all based on the NIST cybersecurity framework, https://www.nist.gov/itl/smallbusinesscyber.[15] And of course, many accounting firms are happy to do this for you, for a fee.[16]

Share prices may not indicate concern over cybercrime incidents. Corporate ESG actions may not indicate concern over cybercrime incidents and even if they do, the third-party warranty used to address that concern, much like the voluntary carbon credits of yore, may be as useful as the extended car warranty I have been trying to reach you about. Care about cybercrime incidents and take steps to secure your firm against them; basic cyber hygiene is not difficult, although it may be tedious and having a plan in place can protect your customers, your clients, your paramours, and whoever else you have stored away on your shared drive. At the very least, delete data you have hoarded that plays no role in your ongoing business operations.

[1] A review of the Amazon appeal as recently as February 2024 shows no real movement to date https://gdprbuzz.com/news/amazon-appeals-against-a-record-e746-million-gdpr-fine/

[2] Figures 3 and 4 are a gross oversimplification to illustrate lost profit and loss in business value calculations, and do not substitute as an expert opinion.

[3] The role aspect here is a product of their poor data security practices, which lead to cybercrime like identity theft, ransomware, data breaches, and more; an underlying foundation for GDPR and other data privacy regulations.

[4] Well, let’s not get ahead of ourselves, “with slightly less importance placed on profitability forecasts,” is probably a more accurate description.

[5] If corporations did not store data to begin with, or at least, stored it in a secure fashion, it would reside at a substantially lower risk level for theft. The method for doing so was established at least in 1985 with David Chaum’s Security without Identification: Transaction Systems to Make Big Brother Obsolete.

[6] ExxonMobil is Suing Investors Who Want Faster Climate Action, February 29, 2024, NPR, https://www.npr.org/2024/02/29/1234358133/exxon-climate-change-oil-fossil-fuels-shareholders-investors-lawsuit, as it appeared May 21, 2024.

[7] Cop28 Finance Leaders Try to Revive Decimated Carbon Credits Market, December 25, 2023, Kenza Bryan, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/c0c6a401-5a15-4446-b4a5-d441193862e6

[8] Cybersecurity in ESG: It’s Time to View ESG and Cybersecurity through the Same Lens, KPMG, 2023, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/ch/pdf/cybersecurity-in-esg.pdf, as it appeared May 22, 2024.

[9] This applies more to engagements as testifying experts, whereas engagements as consulting experts have a bit more calculation to their disclosures.

[10] Go ahead and take some time to read your user agreement for that service.

[11] Locate Family is a data aggregator and seller of personal information and was fined about $600,000; it has revenue of less than $5,000,000 according to https://www.zoominfo.com/c/locate-family/358702539 and https://vpnoverview.com/news/privacy-watchdog-imposes-half-a-million-euro-fine-on-locatefamily/, as it appeared May 22, 2024.

[12] Five different fines levied between January 2019 and December 2020 total $195,000,000 against its 2019 and 2020 revenue of $181.69 billion and $106.74 billion, respectively. Revenue source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/266206/googles-annual-global-revenue/, as it appeared May 22, 2024.

[13] ANSPDCP (Romania) – Fine Against Property Owners Association, https://gdprhub.eu/index.php?title=ANSPDCP_(Romania)_-_Fine_against_a_Property_Owners_Association&mtc=today, as it appeared May 22, 2024.

[14] https://www.timelex.eu/en/blog/first-gdpr-fine-belgium-eu-2000-imposed-mayor, as it appeared May 22, 2024.

[15] This is the one required to be used by service providers to the U.S. government and any organizations providing services to the service provider.

[16] Accounting firms feel they are particularly suited for cybersecurity assessments or creating cybersecurity plans because the skillset applied is very similar to auditing; an oversimplification of which is to create a list of checkboxes, then regularly review those checkboxes, and check them off.

Dorothy Haraminac has performed traditional financial forensics and blockchain forensics for over a decade. She has testified as an expert on crypto tracing and value in multiple jurisdictions. She serves on several boards, has written extensively about crypto litigation, and is the country’s foremost expert on crypto tracing in civil litigation. She was an adjunct professor at Houston Christian University where she taught Software Engineering, Cybersecurity and Digital Forensics courses. She holds a Master Analyst in Financial Forensics credential, holds a Certified Fraud Examiner credential, holds a Certified Cryptocurrency Investigator credential, has earned a master’s degree in Decision and Information Science, and is a licensed private investigator in Texas.

Ms. Haraminac can be contacted at (346) 400-6554 or by e-mail to admin@ybr.solutions.