The Role of Forensic Accountants

in Detecting Fraud in Business Interruption Claims (Part II of II)

Business interruption claims are generally closely scrutinized by insurance carriers and can range from thousands of dollars, to claims exceeding $100 million. Insurance carriers often seek the assistance of either internal or external forensic accountants to analyze such claims. During their analysis, forensic accountants often detect the possibility of fraud in a claim, prompting further investigation by the carrier. This second part presents a business interruption case example that illustrates how to analyze business interruption fraud claims and explains the considerations by insurance carriers when hiring external accountants.

Business Interruption Case Example

A convenience store that specialized in Twinkie sales (Twinkie, Inc.) submitted a claim to XYZ Insurance Company with the following details:

- On January 1, 2021, a fire began in the building after business hours and burned the store to the ground

- The owners completely rebuilt the store and replaced all inventory, supplies, and furniture

- The store was closed from the date of the fire until the rebuilding was complete on December 31, 2021

What is the Amount of Loss?

Upon receipt of the assignment, the forensic accountant will generally research the business, the market, the competitors, market trends, and the general economy of the region where the business is located. Below are examples of documentation and information from the carrier and business that the forensic accountant may request:

- Copies of the insurance policy and related documents[1]

- Copies of the interruption claims made to date

- Information about the peril

- Information about the business (including financial statements for monthly and annual periods)

- Federal tax returns

- Fixed asset depreciation schedules

- Organization charts and payroll records

- Sales and purchase logs with monthly, weekly, or daily totals

- Support for property repair costs

- Expense details and supporting documentation

- Analysis of saved costs

- Bank statements

- Operating agreements

- Production or occupancy records

- Projections and loan proposals

- Personal tax returns and balance sheets[2]

- Accounting source documents

- Outside reports

- Details about past unusual events

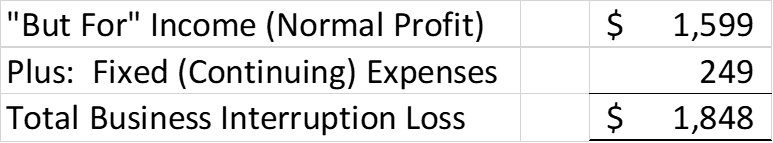

Generally, when calculating a business interruption loss, the first step is to determine the amount of income the business would have made “but for” the loss. The second step is to calculate the actual loss. The actual business loss claim is calculated as the difference between the “but for” income and the actual income.

There are three methods to calculate a business interruption loss as follows:

- Add the “but for” income to the fixed (continuing) expenses over the period of loss

- Subtract the variable (non-continuing) expenses from the lost revenues over the period of loss

- Subtract the actual income from the “but for” income over the period of loss

In all three methods, the period of loss needs to be ascertained. In this example, the period of loss:

- Begins on the date the business was first interrupted

- Ends on the date of full restoration

- Therefore, the period of loss is January 1, 2021, through December 31, 2021, or one year

The next step is to examine historical trends leading up to the period of loss:

- Determine if the business has seasonal trends and/or other significant revenue fluctuations

- In this example, the business has seasonal trends around the December holiday season

The next step is to project sales growth for the period of loss:

- Analyze the historical growth trends to determine the company’s compound annual growth rate

- Examine the company for factors that may impact growth

- Examine industry trends and forecasts

After the completion of the above analysis, the next step is to review findings before proceeding with the financial statement analysis and loss calculations:

- Determine what additional documents are necessary

- Determine what calculations must be performed

- Assess whether (to date) there has been evidence or indications of fraud or misstatements

- Assess other potential risk factors

- Determine how to ‘sanity check’ the numbers for reasonableness and reliability

- Were the financial results audited or reviewed by an outside accounting firm?

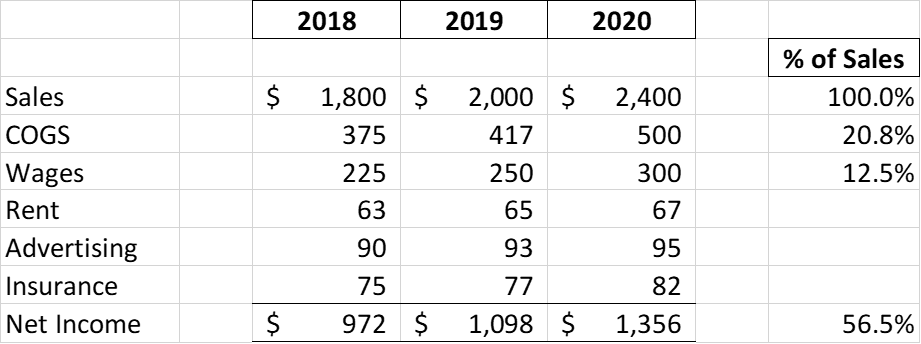

The following step is to analyze the historical financial statements and compute the historical compound annual growth rate (CAGR). Twinkie Inc.’s historical income statements for the years ended 2018, 2019, and 2020 are shown below:

The CAGR is generally calculated using the formula below:

CAGR = (FV/PV) ^ (1/n) – 1

Based on the above formula, Twinkie’s CAGR from 2018 to 2020 is 15.47%.

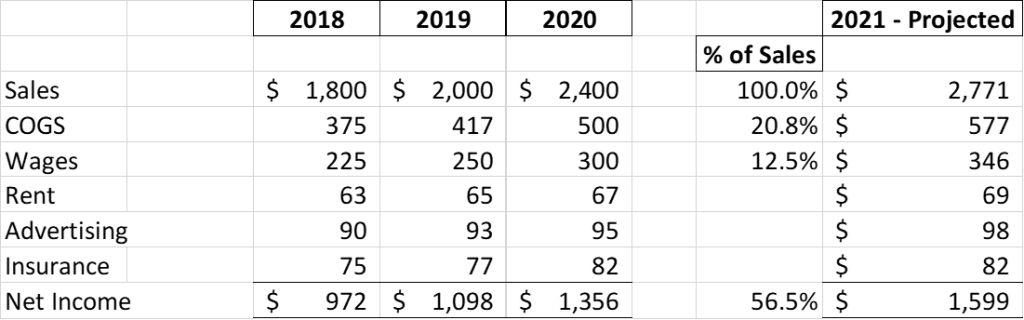

The next step involves identifying the company’s fixed (continuing) and variable (non-continuing) expenses. The goal is to determine each variable cost’s historical percentage relative to sales and to establish the fixed costs during the loss period.

In this example, Twinkie’s rent, advertising, and insurance costs appear to be fixed (continuing) costs. Therefore, the forensic accountant would only expect small variations in these costs for any projected increases in sales.

For this analysis, increase projected sales for fiscal 2021 by the CAGR and calculate the cost of goods sold (COGS) and wages by the historical percentage of sales as follows:

The final steps are to assess reasonableness and reliability of the calculated results. Below is a non-comprehensive list of questions that the forensic accountant and the insurance company should consider:

- Were the sales lost or just delayed?

- Were sales made from existing inventory and was damaged inventory paid at the selling price? If damaged goods were sold at the selling price, it could erode the business interruption claim.

- Were make-up sales made later?

- Do the loss calculations match the overall sales trends?

- Any significant anomalies or unexplained variances?

- Was the seasonality of the business accounted for in the loss calculations?

- Were lost sales due entirely to the peril or were there other factors?

- Were potentially lost sales diverted to other business interests or facilities?

- Is the loss calculation reasonable?

- Were the assumptions contained within the loss calculations reasonable?

- Is the compound growth rate sustainable?

- Is the claimed loss reasonably likely to have been attained or just “probable”?

- How does the loss compare geographically with historical amounts?

- Have fraud risks been identified or has fraud been detected that may require further investigation? If so, consult with the insurance carrier to determine next steps.

In this example using the first method, the business interruption loss for Twinkie, Inc. is calculated as follows:

Analysis of Potential Red Flags in Business Interruption Claims

Fraud risk is listed last in the items above for the forensic accountant and the insurance company to consider, but such risks are certainly not the least important. In the Twinkie, Inc. example, there are several areas where a forensic accountant may uncover “red flags” of potential fraud, including:

- Adjustor or vendor discovery

- Claims history

- Commercial software products

- Tips and employee hotline numbers

- Financial statement analytical review

- Vendor analysis

- Benford’s Law analysis[3]

Other specific analysis for Twinkie, Inc. may include the following:

- Investigate historical revenues

- Do the financial statements reconcile to the tax returns? Fraudsters are less likely to misstate tax returns due to the fear of IRS penalties and possible jail time.

- Does the business have significant uncollected accounts receivables or are the receivables significantly past due? It is not uncommon for business owners to NEVER write-off accounts receivables which may significantly overstate actual revenues.

- Do the company’s revenues reconcile to the cash ledgers? If the company is recording significantly more revenues than cash collections, there may be fictitious revenues.

- Investigate historical expenses

- Do the expense ratios reconcile to industry standards? Does the business contain multiple corporate entities? It is common to see business owners transfer expenses to other business entities to demonstrate profitability for lenders, etc.

- Is the business paying its expenses? If the company is having cash issues, it may accrue expenses on its financial statement but never pay them.

- Investigate operations

- Is the business open and operating? The forensic accountant will often conduct a site visit of the business to make sure it is operating and that the business assets and inventory remain in place.

If fraud is suspected (or detected) by the forensic accountant hired to conduct the business interruption claim, then the client/insurance carrier should determine whether further investigation is warranted. Since a fraud investigation is generally outside the scope of the forensic accountant retained for the original business interruption analysis, the insurance carrier may utilize their own Special Investigation Unit (SIU) team or retain outside forensic accountants to assess the potential fraud issues. In either case, the investigation is generally conducted in three phases:

- Phase I

- Analytical review

- Interview friendly witnesses

- Document examination

- Phase II

- Focus on issues developed in Phase I

- Interview neutral and adverse witnesses

- Examine additional documents

- Phase III

- Interview target(s) of investigation

The interview of the target of the investigation is generally conducted last so that the forensic accountant has all available information prior to the interview. This process makes it difficult for the target to either lie or conceal additional relevant facts.

According to the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB), other general indicators of insurance fraud in the inventory loss areas may include the following:[4]

- Inventory Loss/Property Insurance Fraud

- Insured is recently separated or divorced

- Losses are incompatible with insured’s occupation and/or income

- Losses include large amounts of cash

- Inventory Loss/Fire Related Fraud

- Pets were absent at time of fire

- Losses include old or non-salable inventory or illegal chemicals and materials

- Insured or insured’s business is experiencing financial difficulties (bankruptcy or foreclosure)

- Investigation reveals no remains of non-combustible items of schedules property (coins, gun collections, or jewelry)

- Fire occurs at night after 11:00 p.m.

- Fire department reports cause is incendiary, suspicious, or unknown

- Inventory Loss/Burglary and Theft Fraud

- Commercial losses occur at site where few or no security measures are in place

- Inventory Loss/Claims Process

- Insured’s lost inventory differs significantly from police department’s crime report

- Insured provides receipt(s) with no store logo (blank receipt)

- Insured provides two different receipts with same handwriting or typefaces

- Insured provides single receipt with different handwriting or typefaces

Conclusion

Business interruption claims can be complex and have areas where fraud exists. It may be customary for the insurance company to utilize forensic accountants with fraud experience to minimize the risks associated with such claims. When brought into such investigations, forensic accountants must know how to recognize the various red flags that indicate possible fraud. In these matters, they must also gain a unique understanding of how the insured’s business works, and how it realizes income, expenses, profit, and loss on a historical basis. Armed with this knowledge and insight into the insured’s financial circumstances, a forensic accountant can detect instances of fraud within a business interruption claim.

We would like to thank F. Dean Driskell III and Peter S. Davis for providing insight and expertise that greatly assisted this research.

[1] The application of policy provisions is generally determined by and communicated to the forensic accountant by the insurance carrier.

[2] Personal tax returns are not generally requested for large commercial claims but may be useful in the assessment of potential fraud issues for smaller family-type business claims.

[3] Benford’s Law analysis is an analytical and statistical tool to predict expected digit frequencies in lists of numbers. Such analysis may be utilized to predict fraudulent activity in large number sets, such as financial statements, general ledgers, etc. A full analysis of Benford’s Law is outside the scope of this discussion.

[4] NICB “Indicators of Property Fraud”.

Dean Driskell III, CPA, ABV, CFF, CFE, MBA, is an Executive Vice President in J.S. Held’s Forensic Accounting / Economics / Corporate Finance practice. He specializes in performing consulting services for clients involved in various types of accounting, economic, and commercial disputes as well as fraud and forensic accounting matters. With more than 30 years of experience in financial analysis, accounting, reporting, and financial management, he has served clients and their counsel in both private and public sectors, providing technical analyses, accounting/restatement assistance, valuation services, and litigation support across a variety of industries, and as an expert witness in litigation.

Mr. Driskell can be contacted at (404) 876-5220 or by e-mail to DDriskell@jsheld.com.

Peter S. Davis, CPA, ABV, CFF, CIRA, CTP, CFE, is a Senior Managing Director in J.S. Held’s Forensic Accounting / Economics / Corporate Finance practice. He has served as Receiver in regulatory matters brought by the SEC, FTC, Arizona Corporation Commission, the Arizona State Board of Education, as well as lenders and shareholders. His areas of expertise include: understanding and interpreting complex financial data, fraud detection and deterrence, and determination of damages. He has provided expert testimony in numerous federal, bankruptcy, and state court matters.

Mr. Davis can be contacted at (602) 295-6068 or by e-mail to PDavis@jsheld.com.