Big MAC

Fresenius is the First (General) MAC in Delaware History (Part I of II)

What did Big Foot, the Loch Ness Monster, aliens at Area 51, and Material Adverse Changes (MACs) in Delaware used to have in common? They all allegedly existed but their existence was never proven. That recently changed with a Delaware Chancery Court judge’s 246-page decision in October 2018 that was affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court in December 2018. Fresenius is the first time a buyer successfully terminated a deal due to a MAC clause in a Delaware court. This (and a follow-up) article summarizes the key financial-related issues and provides a financial analyst’s perspective on this landmark case.

Introduction

What did Big Foot, the Loch Ness Monster, aliens at Area 51, and Material Adverse Changes (MACs)[1] in Delaware used to have in common? They all allegedly existed but their existence was never proven.[2]

That recently changed with a Delaware Chancery Court judge’s 246-page decision in October 2018[3] that was affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court in December 2018.[4] Fresenius is the first time a buyer successfully terminated a deal due to a MAC clause in a Delaware court.

This (and a follow-up) article summarizes the key financial-related issues and provides a financial analyst’s perspective on this landmark case.

Overview of the Dispute

This case is about a merger agreement dated April 24, 2017, in which Fresenius Kabi AG (the Buyer) agreed to acquire Akorn, Inc. (the Seller) for $34 per share, which valued Seller’s equity at $4.3 billion. Seller is a specialty generic pharmaceutical company. Buyer is a wholly owned subsidiary of a German healthcare company with a U.S. presence. The deal was expected to take a while to close due to the need to get antitrust approvals.

Seller agreed to acquire Buyer, but closing the deal was subject to certain conditions. One of these conditions was that Seller did not suffer from a MAC. Buyer gave notice on April 22, 2018 that it was terminating the merger agreement, in part, per its right under the MAC clauses. Seller countered with a lawsuit that demanded specific performance: Buyer acquire Seller for $34 per share. The Delaware Chancery and Supreme courts had to decide this issue.

What are MAC Clauses?

MAC clauses are contractual provisions included in sale agreements. In theory, MAC clauses protect the buyer—at the seller’s expense—by ensuring the buyer gets what it paid for (i.e., there were no material adverse changes from the acquired business’ represented condition). However, in practice, buyers historically were unable to use MAC clauses to terminate a deal in a Delaware court.

Fresenius addresses two types of MAC clauses: (a) General and (b) Regulatory. The General MAC clause pertains to a *material* decline in Seller’s business due to *certain* reasons. The Regulatory MAC clause addresses Seller’s materially inaccurate regulatory compliance-related representations.

This article covers the General MAC clause, which is the clause that is typically debated in MAC-related litigation. A follow-up article will address the Regulatory MAC clause.

How is Material Defined?

MAC clauses are frequently discussed but the key word (material) is rarely defined. Vice Chancellor (VC) Laster observed: “[d]espite the attention that contracting parties give to these provisions, [MAC] clauses typically do not define what is ‘material’…What constitutes an [MAC], then, is a question that arises when the clause is invoked and must be answered by the presiding court.’’[5] This approach to defining material may remind some of Justice Potter Stewart’s approach to defining obscenity: “I know it when I see it.”

Why is it Difficult to Define “Material” for MAC Clauses in Contracts?

The footnotes (#525 thru #528) to VC Laster’s opinion, which include excerpts from various texts, provide some interesting context for why “material” is typically undefined in contracts. For example, “[s]etting a [quantitative] threshold for all possible [adverse changes] would seem impractical, and addressing only a limited number could be arbitrary.”

What Must a Buyer Do to Establish the Magnitude of the Effect Was Material?

As a practical matter, a buyer (who has burden of proof) must establish that the decline was (a) large and (b) sustained. The follow-up questions are (a) How large? and (b) How long?

There are no specific answers to these questions. However, based on treatises and case precedent inside and outside of Delaware, there is some guidance that VC Laster summarized. Based on that context, it may be fair to say that a noncyclical decline in profits of 40% or more that is expected to last for a few years would be large and long enough. Perhaps a somewhat smaller decline in noncyclical profits would suffice if it was expected to last for several years. Similarly, perhaps a somewhat shorter decline period would suffice if the decline in noncyclical profits was (much) larger than 40%.

From a financial analyst’s perspective, the decline in Seller’s business value appears to be the best metric. A focus on the valuation-related decline would allow for the comparison of different sizes and duration of declines in profits (and other valuation drivers) on an apples-to-apples basis.

Notably, VC Laster considered the decline in the valuation of Seller’s business (as measured by equity analysts) as “additional support” for the General MAC.[6] As will be discussed in the follow-up article, VC Laster considered a 20% decline in the valuation of Seller’s business due to regulatory-related issues to be material when assessing the Regulatory MAC.

How Did Buyer in Fresenius Establish the Magnitude of the Effect Was Material?

VC Laster said Buyer’s testifying expert “testified credibly and persuasively that [Seller’s] financial performance has declined materially since the signing of the Merger Agreement and that the underlying causes of the decline were durationally significant. The factual record supports [Buyer’s testifying expert’s] opinions.”[7]

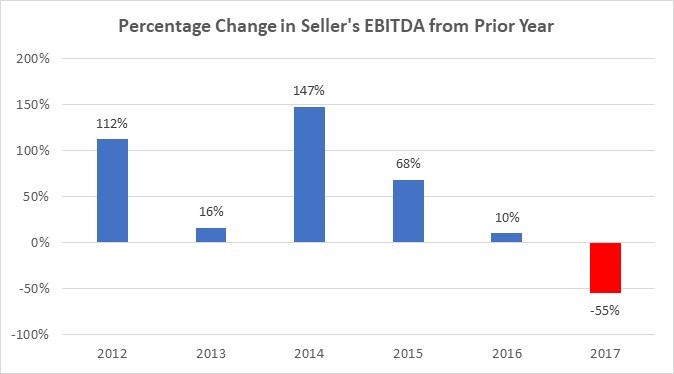

It seems fair to say Buyer’s testifying expert’s opinion and the factual record can be summarized by the two charts—which demonstrate that Seller’s “business performance fell off a cliff”[8]—in Figure 1:

Figure 1[9]

The left chart in Figure 1 shows a very large and sudden adverse change (55% decline in EBITDA after years of substantial growth in EBITDA) in 2017. Notably, VC Laster observed that Seller’s “performance during the first quarter of 2017—before the Merger Agreement was signed—did not exhibit the downturn that the ensuing three quarters did.”[10]

The right chart in Figure 1 shows the year-over-year quarterly changes, “which minimizes the effect of seasonal fluctuations.”[11] There were large declines in each metric (EBITDA is not included because Seller did not report EBITDA on a quarterly basis during 2017).

The decline in Seller’s business was “durationally significant.” The charts in Figure 1 show the large decline lasted for four quarters. Additional evidence indicated there was “no sign of [the large decline] abating.”[12] “More importantly, [Seller’s] management team has provided reasons for the decline that can reasonably be expected to have durationally significant effects.”[13] Thus, the material decline was expected to last for several years.

For additional support, VC Laster also observed that Seller’s equity value declined by 63% to 84% when (a) the $32.13 per share valuation prepared by Seller’s financial advisor when Seller’s board approved the merger is compared with (b) the $5 to $12 per share valuation provided by equity analysts after Seller’s business declined.[14]

Why Aren’t All Material Causes of a Seller’s Adverse Change Considered in MAC Clauses?

The allocation of risks between buyer and seller is based on negotiations that are codified in a contract. “The typical [MAC] clause allocates general market or industry risk to the buyer, and company-specific risks to the seller.”[15] VC Laster explained: “[f]rom a drafting perspective, the [MAC] provision accomplishes this by placing the general risk of an [MAC] on the seller, then using exceptions to reallocate specific categories of risk to the buyer.”[16]

Who Has the Burden to Identify which Risks are Company-Specific?

It is not entirely clear who has the burden. VC Laster (perhaps conservatively) assumed Buyer had the burden. However, he said the following two-step approach would be “preferable and more nuanced.”[17] First, Buyer should have the burden to establish a material decline occurred. Second, after Buyer meets that burden, Seller should have the burden of proving the cause of the decline fell into one of the exceptions. Perhaps this issue will be debated in future MAC-related cases.

How Did the Court Establish Most of the Material Change Was Due to Company-Specific Reasons?

It was an interesting debate. The large decline in Seller’s business performance was primarily due to unexpected new competition that led to price erosion and the loss of a key contract. Seller argued those are industry-related drivers, but VC Laster concluded they were company-specific drivers because they pertained to Seller’s product mix. Reasonable people may disagree over how to make this determination.

Presumably to address the potential ambiguity, VC Laster also considered, for the sake of argument, that the drivers of the material change were industry-related. The next step is to determine if these industry-related drivers affected Seller disproportionately. VC Laster concluded “[t]he record evidence shows that [Seller’s] business has suffered a decline that is disproportionate to its industry peers.”[18]

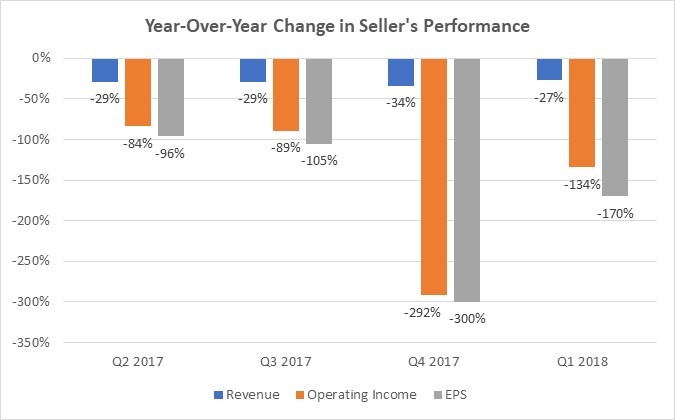

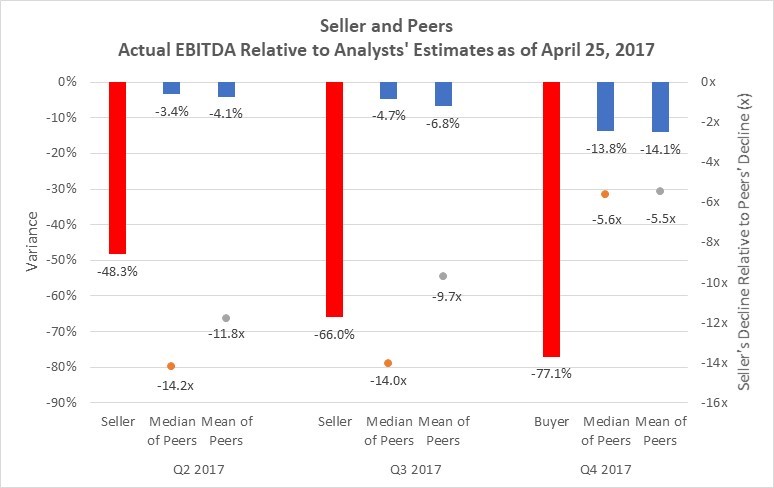

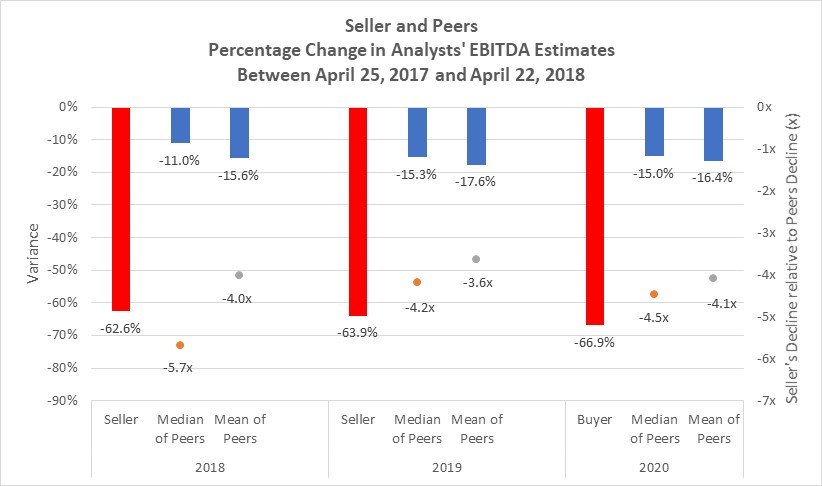

It also seems fair to say Buyer’s testifying expert’s opinion and the factual record can be summarized by two charts, this time contained in Figure 2:

Figure 2[19]

Both charts in Figure 2 clearly demonstrate the decline in analysts’ forecasts for Seller was disproportionate relative to Sellers’ peers. Presumably to mitigate debates over identifying peers, Buyers’ testifying expert used the peers contained within the fairness opinion provided to Seller.

The left chart in Figure 2 compares actual EBITDA during the last three quarters of 2017 with analysts’ estimates as of the date the deal was signed. The variance for Seller was orders of magnitude greater than (i.e., 5x to 14x) the variance for its peers during this period that spanned three quarters of a year.

The right chart in Figure 2 compares analysts’ estimates for the 2018 thru 2020 period as of the date the deal was signed with updated analysts’ estimates as of the date Buyer gave notice that it would not close. This comparison captures a longer-term (three additional years) outlook. The variance for Seller was also orders of magnitude greater than (i.e., typically more than 4x) the variance for its peers.

It appears, from VC Laster’s persective, that Seller punted on addressing this issue through financial analysis presented via live witnesses at trial. VC Laster observed that Seller’s testifying expert at trial recognized that Seller underperformed relative to its peers and “offered no opinion on whether the performance was disproportionate.”[20]

Instead, Seller argued that Buyer was aware of the industry-related risks when it agreed to buy Seller for $34 per share. VC Laster did not concur with that approach, as he focused on whether the decline in Seller’s business was disproportionate. VC Laster also observed that Seller conceded the issue by “[i]ronically…asserting that [Seller] was particularly exposed to the risk of these [industry] headwinds.”[21]

The “particularly exposed to the risk of these [industry] headwinds” point is interesting. On the one hand, Seller has a point as some companies are more exposed to industry-related risks. On the other hand, that argument can only go so far. It is one thing to say a company has incremental exposure of say 20% (e.g., 1.2 beta for the seller vs. 1.0 average beta for its peers). It is quite another to credibly argue declines that are more than 300% greater than its peers (as shown in Figure 2) are industry-related.

Can Equity Analyst Projections Be Used?

This was a contested issue. Seller highlighted in its appeal that the merger agreement stated failure to meet equity analyst forecasts could not be used to determine a MAC.[22] This is important because Seller highlights in its appeal that VC Laster’s “proportionality analysis was based exclusively on third-party analyst forecasts.”[23] VC Laster acknowledged that clause but highlighted two exceptions: (a) the underlying cause of missing the projections can be used for MAC purposes and (b) the projections can be used for MAC purposes if it shows a disproportionate effect on Seller.[24]

As a practial matter, some forward-looking metric is required to measure the change in Seller’s financial performance relative to its peers in order to assess whether the company-specific decline is expected to be durationally significant. A comparison of equity analyst projections, if they arrive at projections for each business in a similar manner, is a pragmatic way to compare apples-with-apples.

No Synergies

An interesting valuaton-related subplot to this case is which standard of value to use. Notwithstanding the large sustained decline in Seller’s profitability, Buyer was still expected to make an economic profit (i.e., generate a return on investment that exceeded the cost of capital) on the deal prior to consideration of the Regulatory MAC. Seller highlighted in its appeal the “odd result that the first [MAC] in Delaware history is an acquisition the acquirer still thinks [is] profitable.”[25]

VC Laster focused on Seller’s stand-alone value, not its value (with resulting synergies) when owned by Buyer. He did so because of the contractual language.

(Note: This discussion pertains to the General MAC. Buyer contends in its response to the appeal that the deal is not economically profitable when the adverse effects from the Regulatory MAC are included.[26])

Delaware Supreme Court’s Opinion

The Delaware Supreme Court issued a very short order that affirmed the Delaware Chancery Court’s determination. This order does not “address every nuance of the complex record.” Instead, it essentially consists of two paragraphs (one for General MAC and one for the Regulatory MAC) that says the factual record “adequately supports” the Delaware Chancery Court’s determinations for each of these MAC clauses.

Some practitioners highlight a nuance in the Supreme Court’s opinion. By modifying “supports” via the inclusion of “adequately,” these practitioners say it may “signal the Supreme Court’s hesitance to fully endorse each aspect of the trial court’s reasoning.”[27]

Closing Thoughts

There is almost always a first time for everything. Fresenius demonstrates that it is possible for a seller to terminate a deal due to the MAC clause.

However, the facts in Fresenius are extreme. Seller’s business fell signficantly further and faster off a cliff than its peers, which is relevant for the General MAC. There were other regulatory-related issues that will be addressed in a follow-up article. One law professor (Brian Quinn from Boston College Law School) commented “[p]rior to this case, the thinking was, there might be a line for MAC…This case is so far over the line that if it weren’t a MAC you should not even write the provision into agreements”[28] Another law professor (John Coates from Harvard Law School) said the “extreme facts” in Fresenius “will probably mean MAC invocation is a rare exception, not the rule.”[29]

It will be interesting to see which case with less extreme facts will be the next example where a seller successfully terminates a deal via a General MAC clause. The demarcation line for establishing when a Seller suffered from a General MAC remains to be seen.

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Duff & Phelps in 2005. Mr. Vitti is a Managing Director in the Morristown, NJ office and is a member of of the firm’s Governance, Risk, Investigations & Disputes business unit. He focuses on issues related to valuation and solvency. This article represents the views of the author and is not the official position of Duff & Phelps, LLC.

Mr. Vitti can be contacted at (973) 775-8250 or by e-mail to michael.vitti@duffandphelps.com.

The author is not an attorney and is not offering legal advice. This article is written from a business valuation practitioner’s perspective, who works on, among other things, litigation-related matters.

[1] The terms Material Adverse Change and Material Adverse Effect (MAE) are often used interchangeably.

[2] For Delaware MACs, proven is in the context of a judge’s opinion.

[3] https://courts.delaware.gov/Opinions/Download.aspx?id=279250

[4] https://courts.delaware.gov/Opinions/Download.aspx?id=282110

[5] VC Laster’s opinion (Opinion) at 118–120.

[6] Opinion at 138.

[7] Opinion at 134.

[8] Opinion at 2.

[9] Left chart: Opinion at 136; right chart: data from Opinion at 135.

[10] Opinion at 136.

[11] Opinion at 130.

[12] Opinion at 137.

[13] Opinion at 137.

[14] Opinion at 138.

[15] Opinion at 121 (citing Zhou, in fn 531).

[16] Opinion at 121.

[17] Opinion at fn 619.

[18] Opinion at p. 145.

[19] Left chart: Opinion at 146; right chart: Opinion at 147.

[20] Opinion at 147.

[21] Opinion at 145.

[22] https://courts.delaware.gov/supreme/oralarguments/download.aspx?id=2895 at 39–40.

[23] Ibid at 39.

[24] Opinion at 126.

[25] https://courts.delaware.gov/supreme/oralarguments/download.aspx?id=2895 at 41.

[26] https://courts.delaware.gov/supreme/oralarguments/download.aspx?id=2925 at 26-27.

[27] https://www.weil.com/articles/delaware-supreme-court-affirms-landmark-opinion-finding-a-material-adverse-effect

[28] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-otc-akorn/the-mac-wall-has-been-breached-should-deal-lawyers-worry-idUSKCN1MC2U3

[29] Ibid.